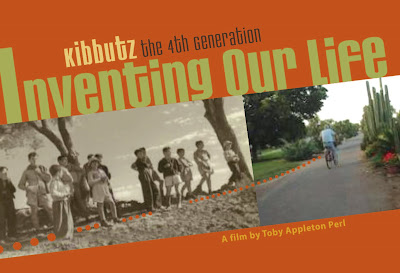

If you see just one movie about the kibbutz, it ought to be Inventing Our Life: Kibbutz—The Fourth Generation. (I’m not saying you should just watch one kibbutz movie; in fact, I’ve seen five in the past few months, with two more on the way—but I realize everyone may not be as obsessive about the history and future of the kibbutz as I am.)

The catch? The film isn’t finished yet.

Toby Appleton, the producer/director, kindly mailed me a “rough cut” of her 82-minute documentary, while she continues to drum up funding to complete post-production. But “rough cut” doesn’t do justice to the diamond she has created. Inventing Our Life is a remarkably compelling work of documentary filmmaking that deserves the widest possible audience.

All of the other kibbutz documentaries I’ve seen so far have been informative, even provocative and well worth watching. However, they tend to focus on an individual community and then contrast its pioneering days with its present struggles. Appleton’s film takes a wider view and examines the kibbutz movement as a key thread within the greater tapestry of the history of the Jewish people and the State of Israel. And yet for all this long view, the film still speaks with an intimacy that strikes an emotional chord in the viewer, thanks to the anecdotes and opinions of the kibbutzniks she interviews. It’s a fine balance between macro-narrative and micro-narrative that Inventing Our Life walks masterfully.

After about 10 minutes of introductory interviews, the storyline loops back to the anti-semitic pogroms in Russia that motivated the Zionist movement and the early founders of the kibbutz to settle Palestine, illustrated by classic footage from a 1920s Zionist propaganda film. Later, members of Kibbutz Sasa, founded by Hashomair Hatzair youth-group pioneers from the U.S., describe their kibbutz-style training camp in New Jersey and then how stories from the Holocaust only steeled their determination to found a Jewish state. Even here, the documentary doesn’t shy from potential controversy:

“This was an Arab village,” one of the founders of Sasa recalls of their arrival to the kibbutz site in 1949. “We had serious qualms about coming to an abandoned village where people’s lives had been uprooted.”

The rest of the film carefully walks viewers through the kibbutz heyday in the 1950s and 1960s (and the vital role of kibbutz soldiers in the Six Day War), while acknowledging that a failure to help assimilate the waves of Jewish immigrants from Arab countries in the years after Independence helped lead to the kibbutz movement’s isolation from the rest of Israeli society, especially after the right-wing and anti-kibbutz Likud came to power in 1977.

The rise of a more capitalist-inclined “me generation” in the 70s and 80s is charted, as well as the financial shock of hyper-inflation and then burdensome debt loads in the mid-1980s, all of which resulted in an entire generation of young kibbutz-born members deciding not to return to their communal homes.

Here, the movie takes on even more complex tones as the issue of privatization (or “renewal”) is raised. We see the question from multiple perspectives, in multiple communities. If the movie has a main focus, it is on Kibbutz Ein Shemer, which is in the midst of hammering out a privatization proposal and debating it amongst its members. Still other kibbutzim appear throughout the film. Kibbutz Hulda, by contrast, has already closed down its dining hall and voted to privatize as a way to draw back young members. Kibbutz Sasa nearly came to the same decision but decided to remain resolutely communal; as one member says, paying different wages for different wages is a “red line” (or what another kibbutznik calls “the Jerusalem issue”) that can’t be crossed: “Anything else, then don’t call yourself a kibbutz.”

Appleton also profiles members of “urban kibbutz” Tamuz in Beit Shemesh about their revisioning of the original kibbutz ideals within an urban context focused on social justice and education. “We are somewhat like Degania in the first days of Degania but more anarchistic,” observes one Tamuz resident. “Cities are where most Israelis live,” says another, “so cities are where real social change must occur.”

One of the strengths of the film is the insight of its articulate interview subjects, which include everyday kibbutzniks but also poets (Avraham Balaban, Eli Alon), philosophers (Avishai Margalit, Yochanon Grinspon) and storytellers (Rakefet Zohar). An ingenious narrative “trick” used by Appleton is to give people’s names, occupations and then indicate which generation of kibbutznik they are but not reveal, until the final few minutes of the film, whether they have remained on their kibbutz or not. Even the composition and lighting of these various interviews are beautifully rendered.

In the end, Inventing Our Life offers a bittersweet homage to the history and future of the kibbutz, one that balances lamentation for its lost ideals (“All dreamers end up on the floor,” says one of the poets) with the possibility for change and the vital importance of the entire project. “I think the kibbutz was the most interesting thing to happen in this country,” says Margalit, “because human beings lack serious experimentation in their lives. I think this was the most dramatic experiment and the most important one.”

Despite the breadth of my own research, I learned a great deal and was fascinated by the archival footage that Appleton unearthed. More impressively, both times I watched the film, I found myself tearing up with emotion by the end, as the “children of the children of the children of the dream” describe the importance of the kibbutz and its altruistic philosophy to their own sense of identity. I challenge any viewer not to be moved by this fine, fine work of documentary art.

And if there are any philanthropists out there who want to invest in an almost-finished doc, drop me a line and I’ll put you in touch with the director.

That’s all for now—I’m halfway to my goal of 100 blog posts to celebrate a 100 years of the kibbutz. More film reviews to come…

How can I obtain a copy of this documentary? I'm also interested in Toby Appleton's "Fifth Generation: Kibbutz at 100" if that's a different film.

Thank you.