Novelist Arthur Koestler (best known for his anti-Stalinist parable Darkness at Noon) was one of the first volunteers to put his memories to paper. He had abandoned his university studies in Germany in 1926, acquired a visa to Palestine and arrived in Haifa with plans to work on a kibbutz, to be a true settler—even though he was an aspiring writer from the city with little taste for physical labour.

Twenty years later, a much-admired journalist and novelist, Koestler returned to the kibbutz and admitted to its members, at a party hosted in his honour, that, yes, he had been a total failure as a settler and deserved to be shown the door. Still, while his restless curiosity had taken him elsewhere, he experienced a pang of nostalgia for the commune that had evicted him. “When I neared the kibbutz,” he wrote, “I felt that, despite the darkness, I had returned to the specific location in the homeland that I could refer to as home.” On that same trip, he visited a number of other kibbutzes to as research for a novel. Joseph, the hero of Thieves in the Night, would share the ironic distance of the author but prove to be a hardier kibbutznik. Through his character, Koestler would get to both relive and rewrite his stillborn experiences as a bumbling volunteer.

Linguist and political critic Noam Chomsky—later a vocal opponent of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza—stayed for six weeks on Kibbutz Hazorea, near Haifa, in 1953 with his wife, where he found a “functioning and very successful libertarian community”. In the years before Israel’s independence, as a young man, he had been deeply interested in anarchist, left-wing politics, and in the socialist vision, shared by many kibbutzniks, of Palestine as a binational state for both Arabs and Jews. He harboured vague aspirations of moving to Israel, joining a kibbutz, and working at Arab-Jewish cooperative efforts. He had no plans, at the time, for an academic career, and his brief stay on Hazorea was a test run for possible immigration to a kibbutz. He worked the fields and found much to admire in the simple life of the commune, as well as the intellectual discussions with the German founders of the community.

Years later, in an interview, the hyper-rational Chomsky sounded ambivalent, even wistful—or as wistful as he must get—about the lost promise of the kibbutz and his brief, youthful experience as a volunteer. “In some respects, the kibbutzim came closer to the anarchist ideal than any other attempt that lasted for more than a very brief moment before destruction, or that was on anything like a similar scale. In these respects, I think they were extremely attractive and successful; apart from personal accident, I probably would have lived there myself—for how long, it’s hard to guess. But they were embedded in a more general context that was highly corrosive.” Even anarchist utopias couldn’t protect their ideals from the outside world.

|

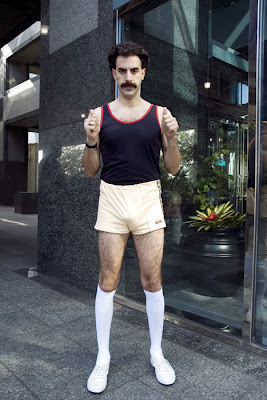

| Borat models 80s-era kibbutz couture |

The nation of Israel changed, irrevocably it now seems, in 1967 in the aftermath of its lightning victory over the massed Arab armies in the Six Day War—and the persistent dilemma of what to do with the Palestinian territories it then occupied. That year also changed the kibbutz movement, by swinging open the gates of these communities—which had always sworn to rely only on the labour of its own members—to volunteers from around the world. Army-aged members had been called up into reserve service during the tense prelude to the war; their positions in the fields and the factories needed to be filled, or the kibbutz economy—and much of Israel’s—would slow to a crawl. The first wave of patriotic Jews from the Diaspora were later followed by hordes of adventure-seeking non-Jews, hippies who had heard rumours of communes in the hills and the deserts of Israel, young Germans burdened by the collective guilt of the Holocaust, and then other backpackers over the next two or three decades.

Actress Sigourney Weaver joined the wave of young volunteers who came to Israel’s aid from America, Britain and other countries in 1967—although her experience on a kibbutz didn’t quite match her imaginings. “I dreamt we’d all be working out in the fields like pioneers, singing away,” she remembered. “We were stuck in the kitchen. I operated a potato-peeling machine.” That assignment nearly ended her acting career before it began; one morning, the peeling machine started coughing and then erupted, showering her with potato shrapnel, as cockroaches swarmed the sudden windfall. “It was one explosion after another,” the star of Ghostbusters and the Alien movies later recalled. “It should have put me off science fiction forever.” Fortunately, it didn’t.

British actor Bob Hoskins, then 25, also volunteered in 1967, and fell in love with the physical work, the sound of the bird calls at sunrise, the romance of rural life. He wanted to remain as a member—except for one hitch. “I was happy being a kibbutznik but they said to me, ‘You gotta join the army’ and I said, ‘But I’m not Jewish’, and they said, ‘It don’t matter’, so I left.”

In 1971, a reedy-limbed, bespectacled, 17-year-old Jerry Seinfield did two months on a kibbutz near the northern Mediterranean coast on a get-to-know-Israel summer program. He hated it. “Nice Jewish boys from Long Island don’t like to get up at six in the morning to pick bananas,” he later recealled. “ All summer long I found ways to get out of work.”

Simon Le Bon, later the lead singer of Duran Duran, kipped for three months in Kibbutz Gvulot in 1979 (and later penned a song called “Tel Aviv”), and his dorm bed was later preserved as a shrine for fans of the dreamy-eyed, swooping-haired, new-wave icon.

Sacha Baron Cohen had been raised in an Orthodox family in London and came, with fellow members of a Zionist youth group, to volunteer on Kibbutz Rosh Hanikra, where Israel’s Mediterranean coastline meets the border with Lebanon. I like to imagine what the kibbutz’s Purim Festival was like when the prankster who became Ali G, Borat and Brüno lived there. Alas, he has never dropped his many personae to talk about his kibbutz experiences, nor has any video evidence surfaced of his stay as a volunteer there.

I’m a member of Kibbutz Shomrat. Many of us are most interested in which kibbutz Bernie Sanders spent time as a volunteer in the 60s. He could be the first Jewish president of the United States.

‘The kibbutz was marvelous. People could do things in which they had no background whatsoever.’

http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/192931/bernie-sanders-story

Hi Moshe:

Thanks for your message & the link! Yes, I'd read that Bernie Sanders spent time on a kibbutz, but nowhere have I found a name or even a general location. The Tablet article gives the most details, although mostly about where his brother stayed & the fact that Sanders stayed for 6 months in Israel and was on one of the "oldest kibbutzim"— and that it did have an influence on his politics as a young man.

Because Larry Sanders first stayed on Matsuva, and arrived after his brother, I wondered if that meant Bernie was staying on a kibbutz in the area. (Maybe Hanita?) Then again, it doesn't seem like the two brothers connected during the two months they were both in Israel at the same time and only discussed their mutual kibbutz experiences much later.

If I was a betting man, and I had to guess which kibbutz he most likely stayed at, my guess would be Mishmar HaEmek: It's in the North but not super close to Matsuva; it's one of the oldest; it was founded by Polish immigrants, like the Sanders' parents; there is no mention in the interview with his bother of Bernie living on the frontier or border (like Kfar Giladi or Hanita), and if it had been a well-known kibbutz like Degania or even Ein Harod, I think it would have been named. But this is just pure speculation on my part!

I'm very curious to know, too, and will ask friends and contacts on Mishmar HaEmek if anyone there has any knowledge of where Sanders did his volunteer time. Let me know if you come across any more clues.

Of course he isn't the kibbutz volunteer to run for president — Michele Bachman lived on Kibbutz Be'eri!

http://www.jpost.com/Diplomacy-and-Politics/Kibbutz-finds-note-from-volunteer-Michele-Bachmann

Shalom,

David