Guy Delisle’s new graphic travelogue, Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012), is framed with images of a plane arriving and then departing. In between, he recounts a narrative of the year he spent in East Jerusalem, Israel and the West Bank with his wife, who was assigned there for Medecin sans Frontieres (and who remains a distant presence, perpetually busy with her NGO work, throughout his book) and two young kids, Louis and Hanna, who occupy far more of his time.

A Quebecois animator and graphic novelist, Delisle strikes a wry, self-deprecating persona: a kind of bumbling house-hubby Everyman, naive, prone to faux pas while also quietly judging people based on how much they know and like comics. In Jerusalem, the world’s most complex city—an urban jigsaw puzzle drawn by Franz Kafka and die-cut by M.C. Escher—he finds an endless supply of paradoxes and ironies to befuddle him. What has become “normal” in Israel, East Jerusalem and the West Bank appears in all its tragedy and folly when described in minute journalistic detail. But the “journalism” practised by Delisle is as much eavesdropping and observing as researching and interviewing.

His sense of bewilderment begins when old Russian man with concentration camp tattoos lifts up and calms his crying daughter on the plane. It continues when he says “Shalom!” to the driver who picks them up at Ben Gurion Airport—and realizes he should have said “Salaam!”

The next day, an MSF officer tries to explain the political-geographical complexities of the city after Guy and his wife get settled into an apartment in East Jerusalem: They are in the capital of Israel according to the Israelis but in the future state of Palestine according to the international community, many of whom consider Tel Aviv the capital of Israel.

“I don’t really get it,” Guy reflects, “but I tell myself I’ve got a whole year to figure it out.”

By the end, though, it’s hard to know if he knows whether he has come closer or farther away from understanding the funhouse mirror chamber of identity and ownership in this densely packed (with people, with cars, with history, with religion) urban space.

He finds himself constantly caught off-guard by the the quirks, the rituals and the conflicts of all three major religions: the wail of the muezzin that wakes his daughter just after she goes to sleep; taking his family to lively West Jerusalem, only to discover it completely deserted on shabbat (“It reminds me of Sundays in Pyongyang,” he says); feeling guilty about munching an apple on Ramadan; the literally and figuratively Byzantine politics of the various Christian denominations jostling for influence (sometimes physically) over the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; or leading a comics seminar for veiled Muslim women, who are studying to be art teachers yet are prohibited by their religion from drawing people or animals.

When he mentions to a shawarma shop owner, in East Jerusalem, that his girlfriend “works for Doctors without Borders,” there is a long pause, as the owner slices off strips of meat, and then replies: “There’ll always be borders.”

Delisle tries to negotiate, as an outsider, the perplexing political nuances of life in East Jerusalem. He checks out a supermarket in a nearby Jewish settlement but resists buying his favourite cereal (Shredded Wheat, which he can’t even get in France) so as not to support the controversial West Bank settlements. But then, as he is leaving, he spots “three Muslim women loaded down with bags”. He visits protests at the checkpoints around the Separation Barrier and sketches the wall obsessively.

He gets moved most noticeably from his otherwise resolute neutrality—more a knowingly ignorant curiosity than high-minded journalistic objectivity—by three separate visits to Hebron: one led by an MSF staffer; another by a member of Breaking the Silence, the NGO that records testimony from Israeli soldiers; and a third by a right-wing religious settler who elides or even contradicts the stories Delisle has heard on the other tours. (The settler mentions only one of the city’s two infamous massacres.) The bitter separation between the tiny Jewish community and the larger group of Palestinian citizens of Hebron is poignantly symbolized by the netting strung over the souk, to catch garbage hurled onto Arab passers-by by angry religious settlers.

The month by month chronology of his family’s year in East Jerusalem gives the book an anecdotal quality, which gains resonance with repeated images or visits to different sites (like Hebron, or the wall, or Tel Aviv). No single incident acquires more prominence—not even Operation Cast Lead, the IDF assault on Gaza midway through his stay, which draws NGOs, like his wife’s, into a flurry of activity. Delisle’s later attempts to negotiate access to Gaza for himself get rebuffed when officials find out he is a comic artist. The imbroglio over the Danish cartoons of Mohammed has been in the news; Delisle also wonders if he hasn’t been mistaken for the more politically motivated comics journalist Joe Sacco.

One mini-chapter that most resonated with me is Delisle’s first visit to Ramallah, driven there by an acquaintance form the Alliance Francaise. “I’m quite surprised,” he notes. “I thought Ramallah would be a dead city, crippled by the conflict.” He meets a Palestinian animator who says it is easier for him to “get to London than travel five km to Jerusalem” for work. A foreign correspondent tells him: “Ramallah is like the Tel Aviv of the West Bank. People are freer and more open-minded here.”

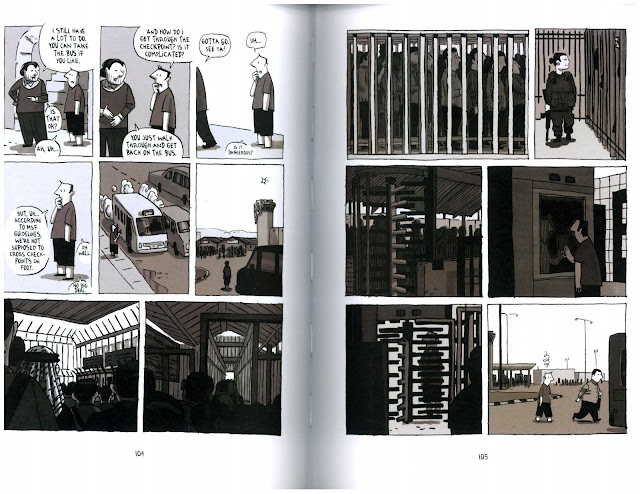

Then Delisle’s acquaintance, who still has other business, suggests he take a bus back through the army checkpoint to East Jerusalem—technically, not allowed under MSF rules. What follows is the darkest page and a half of the book (literally, in the inky shadowing of the frames): 10 panels, without any text, in which Delisle depicts his claustrophobic point-of-view amid the crush of people queued to pass through the barred-in checkpoint for bus and foot traffic through the Qalandia checkpoint. (It immediately brought back my own memories of an hour and a half lined up at the same checkpoint.) He emerges into the light from the prison-like enclosure with a swirl of incomprehension over his own cartoon head.

That scene could be a metaphor for the book as a whole: a wise narrative filled with insightful observations that only prove how darkly puzzling and incomprehensible life in the holy—and wholly divided—city of Jerusalem really is.

Jerusalem is a must-read for anyone interested in this part of the world. (Download a preview here.)

I realize, of course, that there is not a single mention of a kibbutz in his book. But that fact is also telling: Delisle’s chronicle is about life in modern Israel, and especially the city of Jerusalem, and the kibbutz, as an institution that long symbolized the modern Israeli, is now increasingly divorced from and irrelevant to this reality.