|

| The film Rex Reed called, uh, “Charming!” |

The screenwriter, Paul Kember, rewrote the script for this 1985 film (directed by Lewis Gilbert, who had been responsible for three of the hammier James Bond outings, as well as Alfie and Educating Rita) from his 1982 play (titled Not Quite Jerusalem—also the film’s title in Britain, I believe). I’d accuse Kember of ripping off my life story for the main plotline—a young, blonde North American takes a year off his studies to seek romance and adventure on a remote communal farm in Israel—except for a few key facts in his defense:

1) The swoop of blonde locks atop lead actor Sam Robards (later of American Beauty and Gossip Girl fame) deserves the Best Supporting ’80s Coif more than my raggedy, Swiss Army knife-trimmed, Miss Clairoled mullet.

|

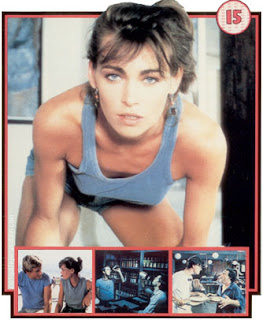

| Joanna Pacula as the fiery kibbutznik Gila |

2) I never had a tumultuous affair with a kibbutznik that left me with a should-I-stay-or-go-to-med-school dilemma, let alone with one as tempestuously sexy as Gila, played (with distinctly choppy English) by Polish-born starlet Joanna Pacula.

3) While I did visit Masada with my volunteer group, we weren’t kidnapped by Palestinian terrorists along the way and rescued by hordes of IDF soldiers in a climactic shoot-out. (The film gives a thanks to the Ministry of Defense in its credits.) Or at least I don’t remember that. I might have been hungover.

4) Oh, and I didn’t go to Israel until three years after the movie came out. So I think Kember is covered.

Nor will I make the case that Not Quite Paradise doesn’t deserve its mediocre 50% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. (Besides, that only means half its viewers liked it, and the other half didn’t; it did, however, get savagely reviewed in the L.A. Times at the time.) Yes, it has an overwrought soundtrack of swooning violins during the corny romantic episodes. (And a gratuitous nipple shot, mandatory in ’80s flicks, for a bedroom scene with the Dome of Rock—or at least a cardboard cut-out of the Jerusalem icon—rising suggestively in the background.)

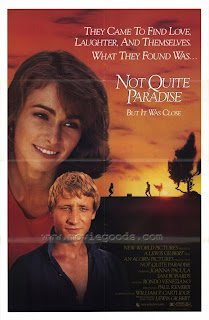

| Didn’t every poster for an 80s comedy look like this? |

Yes, some of the comic stereotypes are egregiously broad, like the icy Finnish twins; or the swarthy, malevolent Palestinian terrorists (the leader played by the recently murdered Jewish-Arab actor Juliano Mer); or Rothwell T. Schwartz, a geeky more-Jewish-than-thou volunteer from the States who annoys the kibbutzniks of apocryphal Kibbutz Azra, amid the bleak yet gorgeous desert surroundings of the Arava Valley (filmed on location in and around Kibbutz Eilot and Grofit), with rhapsodies about his cultural pilgrimage to the Promised Land of his people. (Their eyes shoot daggers when he announces, “My father’s money helped build this country.”)

Many of the broad caricatures of life as a kibbutz volunteer, though, are rooted in truth. Kember must have been a volunteer before he wrote his play and script. Yes, our shorts were that short (Adidas gets thanked in the credits, too), our jeans were that tight and that high-cut above our ankles, and the free cigarettes handed out were that toxic. (“No wonder they’re free,” complains a character. “You get cancer just looking at them.”)

Kevin McNally (who went on to many other roles, including a recurring part in the Pirates of the Caribbean series) plays Pete, a whingeing yet funny British volunteer (there were plenty in my time) who nearly gets booted off the kibbutz when he and another buddy moon an audience of kibbutzniks at a volunteer talent show. (I heard a similar tale about a crew of Brits who offended kibbutz members by dressing as Jews and Arabs and then performing a Full Monty “Dance of the Balloons”; they only survived the calls to expel them because it was the festival of Purim.) His British friend—a Liam Gallagher lookalike called Dave—suffers “volunteer’s asshole” after the dietary switch from English “cuisine” and proves even more annoying than Pete. Both end up becoming kibbutz heroes after one of the film’s few plot twists.

|

| Action! Romance! |

Gila and Michael, the young American played by Robards, try to keep their affair under wraps, even though Gila knows that secrets are impossible to keep in her small, gossip-filled community: “A kibbutz is 200 people,” she warns, “and 2,000 mouths.”

And the reasons for the volunteers coming to Israel are realistically varied: some come to escape the bleak climate, both meteorological and economic, of grotty old England; some come to connect to their ancient heritage; others come for a good time and a break from their studies. And two of the volunteers in the film are running from troubled pasts and psychic traumas—which was often the case, at least in my experience. Psychological breakdowns amongst kibbutz volunteers weren’t just Hollywood plot devices to add drama to a romantic-comedy. They were semi-regular occurrences. It was a place where a lot of buried secrets emerged.

“Volunteers!” scoffs Dave the Brit at one point. “The world’s rejects!”

A bit harsh perhaps. But as the movie suggests in its closing scenes, the kibbutz of the 80s was also a place where bumblers and dreamers, geeks and wanderers from around the world could, for a brief time together, find common cause and create their own eccentric little home away from home.

While I’d never heard of Not Quite Paradise before I went to Israel, apparently the movie did inspire at least some viewers (likely Brits) to make the leap and volunteer on a kibbutz—as one website by a former volunteer and fan of the movie makes clear. And watching the movie is like eating a Proustian madeleine (with a higher cheese quotient) for those of us who lived on one: an almost instant evocation of buried memories and emotions. And bad fashion choices.

Nice one. I was on two kinbutzim in the 90s, this film manages to encapsulate the feelings of it all.

The movie made me aware of Kibbutz and I also went to two during the nineties. Wonderful memories…

That movie changed my life.Saw it in late 86 was in Isreal 87 89 91. The travel bug got hold of me. Finally got some roots down 20 years, half the world and a hell of a lot of fun later.