That was the text, in sea-blue diagonal lettering, across the dirty white tourist T-shirt I was wearing when I arrived home, to Ottawa International Airport, after eight months in the Middle East (and two more weeks in England). I had been living in Israel, but memories of Egypt were fresh in my imagination; I had backpacked with friends for nearly three weeks through the country before flying to Heathrow from Tel Aviv. It remains one of my most memorable travel experiences, even 22 years later, and the sensations and encounters from that trip have been rekindled by the TV images of Cairo alight with protests and retaliation, as the Egyptian people take to the streets to demand the freedoms I took for granted (still do, in fact) as a naive 21-year-old tramping through their homeland, with a bad mullet and a Labatt’s Blue cap.

I remember, after the subtle tensions and dangers of travelling through Israel, amidst the first Palestinian Intifada or “Uprising” (I got, quite literally, stoned in Jerusalem), the sense of relief and relaxation when we dropped our backpacks (mandatory Canadian flag sewn on) in a bare, basic room in Dahab, on the Sinai coast, and enjoyed the laidback hospitality of the locals there: swam in the Red Sea, ate in open-air restaurants, haggled with the Bedouin merchants. I remember camping on the beach in Taba one month when that stretch of sand, south of Eilat, was in Israeli hands, and then passing through it again, a few months later, after it had been turned over to Egypt—the last act of land exchange in the enduring peace treaty between the two former enemies.

I remember the absolute madness that is Cairo. Honking and exhaust and urban chaos like I’d never seen before—not in the bureaucratic orderliness of Ottawa, not after seven months on a remote rural commune. (Lima, Peru, is the closest I’ve come to it since.) Cars roaring five abreast in four lanes. Taxi drivers who could outduel NASCAR heroes. Buses that only slowed down, didn’t actually stop, enough for passengers to leap and hit the ground running (or simply hit the ground). I remember the sublime moments that pierced this urban cacophony. The sun dropping over the Nile, lighting up the haze that embraced the city. Passing an open doorway and witnessing a wedding crowd, with three musicians blowing long trumpets, and a tall man whirling like a dervish, spinning and raising elaborate skirts that ringed his waist, one after the other, over his head, as the wedding party sang and clapped. Or the National Museum stuffed to its ceiling with the antiquities of the pharoahs.

I remember the small absurdities of travel—those silly details and gaffes that stay with you when seemingly more meaningful, more profound experiences fade from memory. The sign across the stone entrance: “The Great Pyramid is closed for restoration.” The quixotic search for a tourist site called “The Unfinished Obelisk”—which, once we found it, we immediately renamed “The Barely Even Freakin’ Begun Obelisk.” The taxi driver with such an insatiable horn-honking habit that, when we hit a rare stretch of empty highway, he still gave his steering wheel a regular, noisy swat, just to stay in practice. Hanging out with a group of Egyptian men, in Luxor, as we waited for fresh bread to emerge from their late-night ovens and listened to them complain about their cackling, bustling boss, who they had nicknamed “The Devil”. Sleeping through our alarm, missing our train to Cairo, and hiring a taxi to chase it down, through the night, from one station to the next, because we couldn’t afford not to catch it. Running around the city, down to our last few dollars, because my girlfriend’s Visa card had been cancelled (and her new one unhelpfully mailed to her home address in England) and I was left to tour almost every bank in Cairo to finally locate a teller willing to cash a traveller’s cheque in Canadian funds—and pay for the bus ride back to Israel.

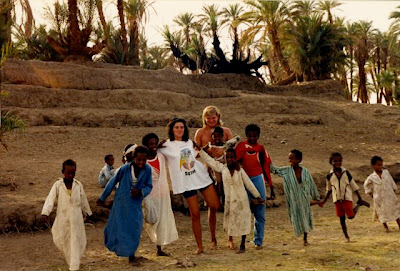

I remember the pairs of young men, well-dressed, as the night air released the heat of the day, walking hand in hand, as male friends do in Egypt, across the bridges in Cairo. Or our felucca captain taking me by my hand, so he could tour me around to his friends in Aswan, as we outfitted his sailboat with pita and vegetables and fruit for our journey down the Nile. I remember stopping in a riverside village, between temple visits, and being surrounded by kids, in raggedy jabiliyehs, and, for a reason that now escapes me, chasing them across the shore while we all hopped on one leg.

There was a liveliness that I experienced during my too brief stay in Egypt. A curiosity that thrummed in the people we met. (“Canada?” they would reply, after asking where I’d come from. “Ah, Canada Dry!”) A desire to talk and to learn and to connect. A democratic spirit, at its core, that had been bottled up even then—one that is now bursting into the streets, defiant, youthful, demanding to be heard.

If “Egypt: No Problem” isn’t exactly the right slogan for this uncertain moment in history, I hope that the citizens of this fascinating, complex nation come through the many challenges ahead and emerge to form a new society where every one of them can fly that same motto proudly.