The Hula Valley extends into the northernmost reaches of Israel, what’s often called the “finger of Galilee”, and borders Lebanon and the Golan Heights. It’s a stunningly beautiful landscape of rolling hills, swamps drained and tilled into lush fields and orchards, and the earliest (and best conserved) flow of the Jordan River, all shadowed by the snowy peak of Mt. Hermon. It was the picturesque backdrop to my life and work for nearly eight months on Kibbutz Shamir. The fiery, lingering sunrises and sunsets are still burned into my memory—and, for that matter, the photo at the top of my blog.

It’s also home to the kibbutzniks of Kfar Giladi, one of the first communal settlements in the area, founded in 1916. Nine decades later, Giladi voted to privatize in 2003. Since then, the landscape—on the opposite side of the valley from Shamir—has remained the same, but the life of its members has changed. Keeping the Kibbutz, a new (and as yet unreleased) documentary from two young American filmmakers, charts those changes and some of the disappointments felt by kibbutzniks left behind by privatization. Co-director Ben Crosbie was born on the kibbutz but moved to the U.S. at age three and visited occasionally growing up. In 2007, he returned to Giladi with his co-director, Tessa Moran, and let their cameras roll as kibbutzniks talked candidly about their feelings and the increasingly market-driven, individualistic management of their once-communal home.

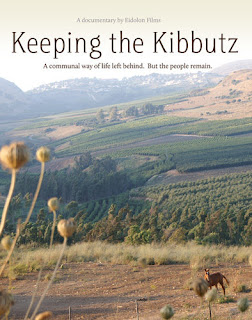

It’s also home to the kibbutzniks of Kfar Giladi, one of the first communal settlements in the area, founded in 1916. Nine decades later, Giladi voted to privatize in 2003. Since then, the landscape—on the opposite side of the valley from Shamir—has remained the same, but the life of its members has changed. Keeping the Kibbutz, a new (and as yet unreleased) documentary from two young American filmmakers, charts those changes and some of the disappointments felt by kibbutzniks left behind by privatization. Co-director Ben Crosbie was born on the kibbutz but moved to the U.S. at age three and visited occasionally growing up. In 2007, he returned to Giladi with his co-director, Tessa Moran, and let their cameras roll as kibbutzniks talked candidly about their feelings and the increasingly market-driven, individualistic management of their once-communal home.The film (Crosbie and Moran generously sent a preview copy to me) begins with a quick introduction to the history of Giladi and the early ideals of the kibbutz movement: the philosophy of “from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs”; the communal child-rearing; the socializing in the dining hall; the collective harvests in the cotton fields. Flashforward to the present: the children have long since moved into their parents’ home, the dining hall is half-empty, day labourers are hired to do field work (and cotton is no longer grown), and everyone gets a different wage—just like the rest of the world.

Many of the kibbutz films I’ve watched seem to follow the famous stages of grieving: Degania (anger and bargaining); Kibbutz (depression). In Keeping the Kibbutz, we get to see kibbutzniks who have reached that fifth and final stage—who have accepted, however reluctantly, the changes that have overtaken their community but still look back with fondness and nostalgia at the unique communal society from which they all emerged.

The film does a sumptuous job of evoking that nostalgia without lapsing into sentimentality, thanks in large part to the humour and honesty that the handful of main interview subjects bring to their experiences. Throughout, the filmmakers juxtapose archival footage and photos with similar contemporary images of farm and fisheries workers, children and parents, to show that for all the changes, there is a continuity of life and community on Giladi.

During the filming, two of the older residents get told that their wages are being cut or their services are no longer needed on the kibbutz, and we see their pangs of self-doubt (or bemused resistance on the part of puckish Frankie, a former lager lout from South Africa who came to Israel to dry out and ended up marrying a kibbutznik) that accompany the loss of the identity they had formed working for their community. Giving retirement-aged members meaningful work was always a key part of the original kibbutz ideal. In fact, the optical factory where I worked at Shamir—and that has since become a multi-million-dollar international enterprise—was originally created as a make-work project for oldsters.

“I’m like excess baggage,” says Frankie when he reads the “Dear John” letter from kibbutz management. “Only you can take care of yourself and your needs,” one of the managers later tells him. He just shrugs and says, “I hate the word ‘money’.”

Uzi, another member, gets laid off from his repair job on the kibbutz—even though he is never given a chance to explain the reason the repair shop never shows a profit in its accounts is because, for decades, the kibbutz wasn’t supposed to make money and therefore fudged its accounting in various ways. “I like to do things for people,” he admits. “This is my god. I don’t need religion.”

In a later scene, Uzi takes one of the filmmakers for a glider ride high above the Hula Valley and viewers get a panoramic sense of why the kibbutz members are so deeply attached to this landscape, so reluctant to leave, even as their community changes from its original ideals. The film is filled with beautiful images of the kibbutz and its hilly environs, evocatively backed by a gorgeous piano and guitar score by composer Preston Hart.

“I love the kibbutz,” says Uzi’s wife, Kathy, who arrived as a volunteer in 1968 and married into Giladi. “It breaks my heart that it has to change. I’m sad that my children grew up in a special society that doesn’t exists anymore.”

But she says these words with a smile on her lips, and not a bitter one. She seems to have accepted the changes, adapted to them even (she “buys” and then runs the kibbutz store), and the film ends with a scene of a backyard barbecue in the last light of dusk, with friends and laughter and a sense of community that has altered perhaps but hasn’t fully disappeared. The old socialist principles have been shed, but the members are still “keeping the kibbutz”.

Check out this trailer for the documentary and watch out for the film at festivals in the coming year…

Can't wait to see it. I spent a few months at Kibbutz Yiftah in 1982 and 1983, some of the happiest moments of my life. So sad these things are disappearing, a form of communism that worked, looked after its elders, made everyone feel they could contribute. Well done on your involvement.

Thanks for your thoughts, Hazel. Yiftah is in the Hula Valley, I believe, so you too must have memories of those sunrises and sunsets. It's hard not to feel nostalgic for those days and those places (I know I do!), although life goes on and changes happen for the people who still live there.

It was a life changing experience. Thanks to all who made it the time off my life. I can never forget the place and the people. CJ Joubert 1994

Can't wait to see the film. Spent 2 years on Kfar Giladi as a volunteer and remember Kathy, Uzi and Frankie very, very, very warmly.

times have changed and people want money.