Feb 16, 2014

During my research, I’ve been curious about the impact of the kibbutz as an idea and an institution beyond the borders of Israel.

Living or volunteering on a kibbutz has shaped the lives of tens of thousands of non-kibbutzniks, of course. But the idea of the kibbutz, as a communal settlement, has never really been successfully transplanted — not on a large scale — outside of the nation where it was founded.

I’d heard that it played a role in shaping the early ideas of the Danish co-housing movement. And I’d stumbled across Jewish summer camps and an art colony and a briefly lived intentional co-op in Seattle that all wore the label of “kibbutz”. Even an eco-resort in Costa Rica. All were relatively small scale. None truly reflected the revolutionary communalism of the original kibbutz.

One of the most intriguing kibbutz-inspired communities is the Agahozo Shalom Youth Village—and, alas, I only learned of it from the obituary notices of its founder, Anne Heyman, who died recently in a horse-riding accident. Heyman had founded the youth village, in Rwanda, as a way to help and to help the many orphans, now adults, who had lost their parents in the horrific genocide in 1994.

Heyman, a New York lawyer and Jewish communal activist who was born in South Africa, viewed Israeli kibbutzes that took in Holocaust orphans as a model for coping with the hundreds of thousands of children orphaned by the Rwandan genocide.

She had looked back at history, to the lost generation of the Holocaust, and how the kibbutz movement had welcomed these orphans into their sanctuaries. She had seen the power of the communal ideal to provide the support — nurturing relationships, meaningful education, and purposeful work — to help repair the unfathomable losses suffered by these children, to help them find a path to a hopeful future out of the darkness of the past.

The Agahozo Shalom Youth VIllage is perhaps the best example I’ve found of the kibbutz dream evolving and taking a new yet equally inspired form in soil far beyond that of Israel/Palestine. It’s so tragic that the woman with the vision to make it a reality has died, so young (just 51), before she could truly see what it might grow into. I only hope that it, too, survives her passing.

Jul 16, 2013

I’ve been shamefully neglecting this blog, while busy with teaching—and also finishing the manuscript whose research this blog was set up to track! In short, the first draft of the book is nearly done. It’s too long—by nearly 100,000 words—but then again, there’s a lot to say about the kibbutz, its 100+year history, and the utopian impulse that continues to spring from this experiment in radical sharing.

Last month, I travelled to the north of Scotland, to the International Communal Studies Association triennial gathering, in the fascinating New Age community of Findhorn—a place that deserves a book entirely of its own. (In fact, it has several.) The last ICSA meeting had been in Israel, to mark the centennial of the kibbutz movement, and it was there that I had met many research contacts and experts in kibbutz studies.

This time, I’d agreed to give a paper on how the lessons of kibbutz architecture and design might be applied to improve the community life and reduce the ecological impact of run-of-the-mill suburbs (like the one I grew up in). It was, to be honest, a reworking of the TEDxVictoria talk I gave in 2011:

I also led a fun workshop / design charrette / hackathon called “Greening the ‘Burbs,” which encouraged participants to brainstorm in groups to generate ideas on how to retrofit suburbia for a greener future. About 20 people took part and came up with wonderful concepts, including neighbourhood “skill-sharing” sessions, “defencing” backyards, edible community gardens, and a “boutique” (like Findhorn’s) where people can drop off unwanted clothes and other goods—and pick up (rather than purchase) “gently used” items. Think of the neighbourliness that develops when you spot someone wearing your old sweater! (Check out all the conference abstracts here.)

In a pique of over-enthusiasm, I’d also agreed to give a literary reading, from my book-in–progress, at an evening event called “The Great Sharing”. The selection I’d brought was a darkly comic excerpt from a chapter about a strange and charismatic German volunteer named Wolf and his raucous birthday party on Kibbutz Shamir—which ended with the night sky lit up by flares, over northern Israel, as the IDF tracked down and killed (as we later read in The Jerusalem Post) several Palestinian insurgents from Lebanon. The chapter was a reminder that for all of our drunken volunteer revels, we were still living in a land forever on the edge of violence. I’d read the excerpt, to good response, at our faculty literary evening last spring.

But then a mini-controversy erupted at Findhorn. And it centered on the kibbutz. And Israel. And the Palestinians.

Even here, in the far north of Scotland, it turned out that this divisive issue could threaten to over-shadow an academic gathering advertised as a way to discuss and promote “communal pathways to sustainable living”….

What happened?

A group called the Scottish Palestine Solidarity Campaign had got wind of the ICSA conference and noted that a number of Israeli academics and kibbutz members were attending. (In fact, the ICSA has been founded and has its main office based in Israel.) They planned to protest. Those of us in attendance noticed something was up when police cars appeared during the opening day of the conference. At one point, two Scottish cops inspected a bulletin board on which photos of every presenter was pinned.

“Are they looking for one of us?” we joked. “Is there a criminal in our midst?”

Details of their “investigation” leaked out. First as rumour, then as fact. The police wanted to make sure any protest was peaceful. The visiting Israelis had been briefed about the SPSC and its intentions.

I never saw a protester in the flesh, but I did spot a couple of cars labelled with signs and fact-sheets putting forward the SPSC’s position. Later, a kibbutz-based professor whom I knew complained that the SPSC website had explicitly targeted him under an article titled “Findhorn Community ‘proudly hosts’ supporters of ethnic cleansing”. Tensions were rising, even if most non-Israelis were largely unaware on the online attacks on the conference and Findhorn. Organizers—already stretched with running a major international conference—were meeting with the SPSC, members of the Findhorn community sympathetic to the Palestinian cause and the Israeli attendees to broker a compromise. An anonymous leaflet about the issue, dropped off (and then quickly removed) on dining-room tables before a meal, only sparked more concerns.

In the end, both the Findhorn Foundation and the ICSA board (which I had just joined) hammered out statements about the controversy. Both were read aloud at the conference’s final event.

And my literary reading? Well, I decided to scratch my name from the reading list for the Great Sharing, an hour before the show. People would likely prefer to hear the musicians do their thing anyway, I figured. I didn’t need to throw fuel onto a fire that was already making kibbutz colleagues feel uncomfortable and was distracting from the discussions about intentional communities and sustainability. (The organizers of both the conference and the talent show both agreed.)

Yes, there is a good panel discussion to be had about the kibbutz movement’s checkered relations with the Palestinian people, the role the kibbutz played in both establishing the state of Israel and (to a lesser degree) extending its reach into the West Bank and Gaza. My book research has dealt, in part, with some of the failures of the kibbutz—and some of the efforts of new utopians and kibbutzniks—to bridge that divide. People like Anton Marks, of Kvutsat Yovel, who was at the conference to talk about the urban kibbutz movement and its social-justice efforts—and who went to prison as a conscientious objector rather than serve in the Occupied Territories. However, I don’t think the SPSC was especially interested in having such a nuanced conversation on the issue.

I’m trying to tackle it in my manuscript, knowing full well that my take on the topic will likely please neither side in a debate in which Black shouts down White and vice versa, while Shades of Grey cower in the corners and try to get a whisper in edgewise.

Perhaps a panel session at the next ICSA conference, in 2016, might tackle the thorny problem of the kibbutz’s relationship with the Palestinian people from a variety of angles, historical and contemporary. It could be a way of moving past the Israeli/Palestinian debate as a litmus test for ideological correctness and instead engaging in a genuine debate about how to build peace by cultivating truly inclusive communities.

Utopian? I sure hope so. Because that’s what the ICSA—and my book—is all about.

Oct 24, 2012

For years, kibbutzes in Israel reliabley delivered the votes of their members to the left-leaning Labor Party (and its predecessors) in exchange for a guaranteed seat in the Knesset and (back in the days when Labor actually formed governments) a hand on the levers of the power. That decades-old wedding may be headed for divorce court.

News out of Israel suggests that the Kibbutz Movement is pissed off by a proposal, by new Labor head and former journalist Sheli Yachimovich, to combine the guaranteed seats for each the Kibbutz Movement and the Moshav Federation into a single seat that would represent the whole spectrum of Israel’s communal settlements. That doesn’t sit well with kibbutzniks, who always saw themselves as more ideologically committed as pioneers than the wishy-washy cooperative farmers on the moshavs—even if most kibbutzes have since “privatized” and operate far more like moshavs (or even gated country suburbs).

The article can’t resist a poke at the puzzling distinction between a kibbutz and a moshav—a huge difference to kibbutzniks but a bewildering hair-splitting to everyone outside their fences:

“An old joke best explains the distinction between a kibbutz and a moshav: if a kibbutznik had enough, he’ll probably move to a moshav (easier communal rules); but if a moshavnik had enough – he sure as heck is not moving to a kibbutz (even more stringent communal rules).”

Of course, the Labor Party bickering, amid polls that show right-wing Benyamin Netanyahu likely to form another coalition in the next election, only underscores the growing disfunction of the Israeli Left and the profound loss of influence (even among traditional allies) of the once powerful Kibbutz Movement.

Jun 27, 2012

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

May 7, 2012

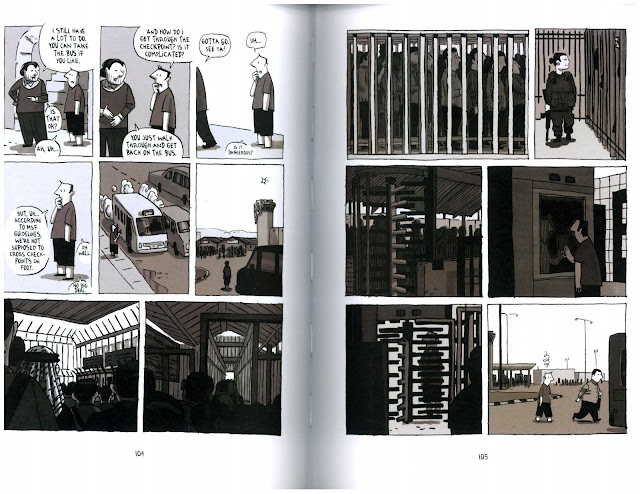

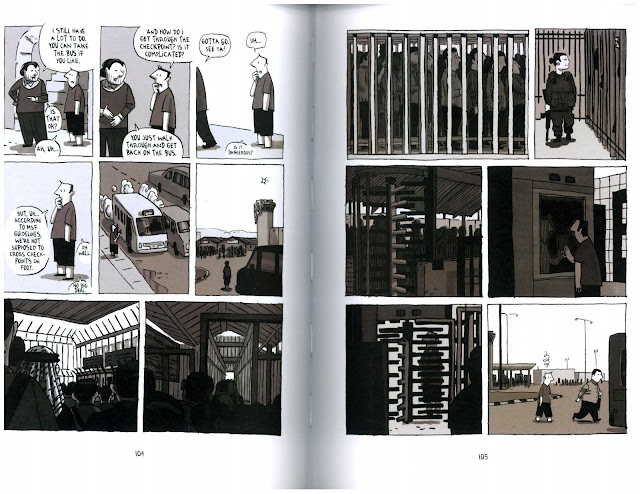

Guy Delisle’s new graphic travelogue, Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012), is framed with images of a plane arriving and then departing. In between, he recounts a narrative of the year he spent in East Jerusalem, Israel and the West Bank with his wife, who was assigned there for Medecin sans Frontieres (and who remains a distant presence, perpetually busy with her NGO work, throughout his book) and two young kids, Louis and Hanna, who occupy far more of his time.

A Quebecois animator and graphic novelist, Delisle strikes a wry, self-deprecating persona: a kind of bumbling house-hubby Everyman, naive, prone to faux pas while also quietly judging people based on how much they know and like comics. In Jerusalem, the world’s most complex city—an urban jigsaw puzzle drawn by Franz Kafka and die-cut by M.C. Escher—he finds an endless supply of paradoxes and ironies to befuddle him. What has become “normal” in Israel, East Jerusalem and the West Bank appears in all its tragedy and folly when described in minute journalistic detail. But the “journalism” practised by Delisle is as much eavesdropping and observing as researching and interviewing.

His sense of bewilderment begins when old Russian man with concentration camp tattoos lifts up and calms his crying daughter on the plane. It continues when he says “Shalom!” to the driver who picks them up at Ben Gurion Airport—and realizes he should have said “Salaam!”

The next day, an MSF officer tries to explain the political-geographical complexities of the city after Guy and his wife get settled into an apartment in East Jerusalem: They are in the capital of Israel according to the Israelis but in the future state of Palestine according to the international community, many of whom consider Tel Aviv the capital of Israel.

“I don’t really get it,” Guy reflects, “but I tell myself I’ve got a whole year to figure it out.”

By the end, though, it’s hard to know if he knows whether he has come closer or farther away from understanding the funhouse mirror chamber of identity and ownership in this densely packed (with people, with cars, with history, with religion) urban space.

He finds himself constantly caught off-guard by the the quirks, the rituals and the conflicts of all three major religions: the wail of the muezzin that wakes his daughter just after she goes to sleep; taking his family to lively West Jerusalem, only to discover it completely deserted on shabbat (“It reminds me of Sundays in Pyongyang,” he says); feeling guilty about munching an apple on Ramadan; the literally and figuratively Byzantine politics of the various Christian denominations jostling for influence (sometimes physically) over the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; or leading a comics seminar for veiled Muslim women, who are studying to be art teachers yet are prohibited by their religion from drawing people or animals.

When he mentions to a shawarma shop owner, in East Jerusalem, that his girlfriend “works for Doctors without Borders,” there is a long pause, as the owner slices off strips of meat, and then replies: “There’ll always be borders.”

Delisle tries to negotiate, as an outsider, the perplexing political nuances of life in East Jerusalem. He checks out a supermarket in a nearby Jewish settlement but resists buying his favourite cereal (Shredded Wheat, which he can’t even get in France) so as not to support the controversial West Bank settlements. But then, as he is leaving, he spots “three Muslim women loaded down with bags”. He visits protests at the checkpoints around the Separation Barrier and sketches the wall obsessively.

He gets moved most noticeably from his otherwise resolute neutrality—more a knowingly ignorant curiosity than high-minded journalistic objectivity—by three separate visits to Hebron: one led by an MSF staffer; another by a member of Breaking the Silence, the NGO that records testimony from Israeli soldiers; and a third by a right-wing religious settler who elides or even contradicts the stories Delisle has heard on the other tours. (The settler mentions only one of the city’s two infamous massacres.) The bitter separation between the tiny Jewish community and the larger group of Palestinian citizens of Hebron is poignantly symbolized by the netting strung over the souk, to catch garbage hurled onto Arab passers-by by angry religious settlers.

The month by month chronology of his family’s year in East Jerusalem gives the book an anecdotal quality, which gains resonance with repeated images or visits to different sites (like Hebron, or the wall, or Tel Aviv). No single incident acquires more prominence—not even Operation Cast Lead, the IDF assault on Gaza midway through his stay, which draws NGOs, like his wife’s, into a flurry of activity. Delisle’s later attempts to negotiate access to Gaza for himself get rebuffed when officials find out he is a comic artist. The imbroglio over the Danish cartoons of Mohammed has been in the news; Delisle also wonders if he hasn’t been mistaken for the more politically motivated comics journalist Joe Sacco.

One mini-chapter that most resonated with me is Delisle’s first visit to Ramallah, driven there by an acquaintance form the Alliance Francaise. “I’m quite surprised,” he notes. “I thought Ramallah would be a dead city, crippled by the conflict.” He meets a Palestinian animator who says it is easier for him to “get to London than travel five km to Jerusalem” for work. A foreign correspondent tells him: “Ramallah is like the Tel Aviv of the West Bank. People are freer and more open-minded here.”

Then Delisle’s acquaintance, who still has other business, suggests he take a bus back through the army checkpoint to East Jerusalem—technically, not allowed under MSF rules. What follows is the darkest page and a half of the book (literally, in the inky shadowing of the frames): 10 panels, without any text, in which Delisle depicts his claustrophobic point-of-view amid the crush of people queued to pass through the barred-in checkpoint for bus and foot traffic through the Qalandia checkpoint. (It immediately brought back my own memories of an hour and a half lined up at the same checkpoint.) He emerges into the light from the prison-like enclosure with a swirl of incomprehension over his own cartoon head.

That scene could be a metaphor for the book as a whole: a wise narrative filled with insightful observations that only prove how darkly puzzling and incomprehensible life in the holy—and wholly divided—city of Jerusalem really is.

Jerusalem is a must-read for anyone interested in this part of the world. (Download a preview here.)

I realize, of course, that there is not a single mention of a kibbutz in his book. But that fact is also telling: Delisle’s chronicle is about life in modern Israel, and especially the city of Jerusalem, and the kibbutz, as an institution that long symbolized the modern Israeli, is now increasingly divorced from and irrelevant to this reality.

May 1, 2012

It was great shock that I read, via Twitter, of the death (at age 60) of Abdessalam Najjar, one of the founders and leaders of Wahal-al-Salam/Neve Shalom—the village of Palestinians and Jews located near the Latrun Monastery. I’d interviewed him, in 2010, and found him a remarkable man: super-smart, funny, wise, an engaging storyteller, and a committed man of peace. I spoke to him for more than an hour, and knew throughout talk that I had to try to squeeze as many of his words as possible into my book (should I ever finish writing it).

Born in Nazareth, Abdessalam—perhaps more than anyone I met on my different trips—exemplified the utopian spirit of the original kibbutzniks. He had taken the path less travelled and chosen to live, in peace if not always harmony, with the people who he’d been taught were his enemy. He had helped to create in the “Oasis of Peace” a model that proved that Arabs and Jews could sit together and talk about their different situations, their competing narratives and grievances, could live together, could go to school together. That the walls of hate (and concrete, too) that had been erected too hastily could be pulled down, brick by brick.

I included a short transcript from our interview earlier on my blog. But Abdessalam had so much more to say—to me, to the world. It is a profound loss to his homeland and for the hope for peace over violence in Israel and Palestine.