Apr 15, 2011

Every child, it seems, is a born utopian. That native urge to create new realms lies dormant for the first few years of life, not needed yet, held in check for more fundamental urges: learning to eat and crawl and babble and poop in a socially acceptable fashion; discerning sense from the 4D sound-and-light-and-smell-and-taste-and-touch show emanating 24/7 from the theatre we’ve been abruptly chuted into.

But as soon as we can hold a block or wield a crayon, as soon as the imagination takes a firmer grip upon the steering levers of consciousness, we begin to build. We build towers, as ambitious and as precarious as any Babel. We build cities, circumscribed by laws laid out by the gods Lego and Mattel. We build societies, with leaders and followers, heroes and villains, with histories and intrigues. Locked in a wider world we can’t quite understand, let alone control, we build our own worlds—private microcosms—over which we can lord.

Like any kid, I had my own peculiar world-building fixations. I laid out streets and engineered neighbourhoods for my stumpy, legless, bullet-domed Fisher Price volk. I played pint-sized Jane Jacobs in the shadows of my parents’ basement. There is an old Kodachrome photo of me as a boy, ever the good Catholic, arranging Star Wars action figures between pews of building blocks so they could attend Sunday Mass at a cathedral; in my world, Boba Fett couldn’t be an intergalactic bounty-hunter without first receiving Communion.

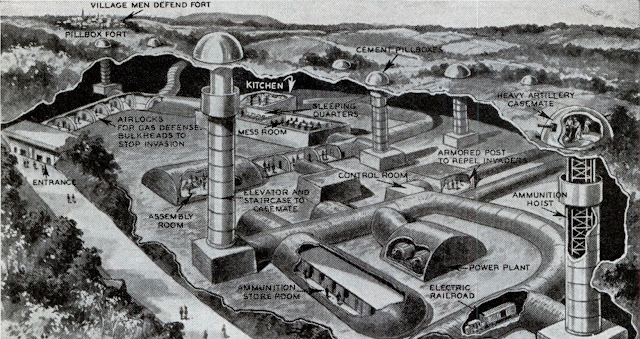

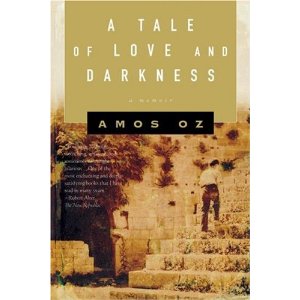

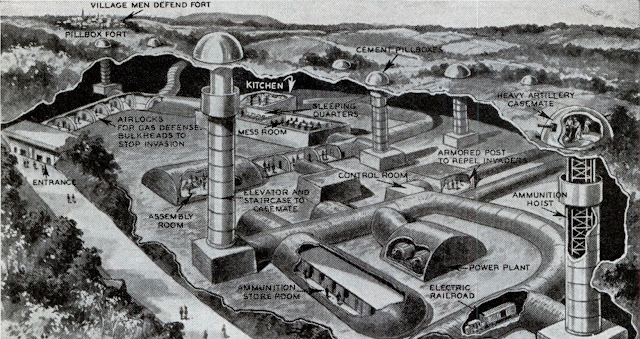

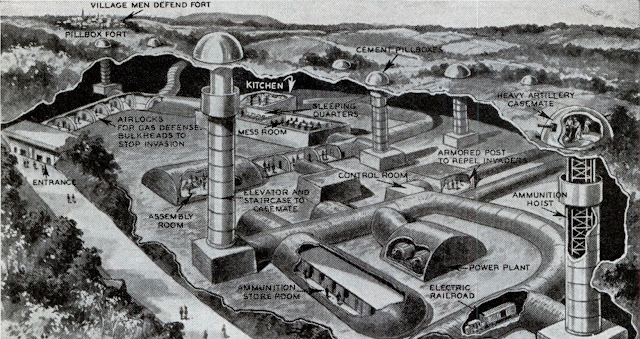

Perhaps my oddest obsession was renovating the Maginot Line. I had read about the French fortifications in an illustrated history book and was particularly struck by the cross-section diagrams of the underground chambers, tunnels and military installations, a vast network of subterranean routes and rooms for a strategically inept nation of mole people. Built in the 1930s to withstand a German assault, at the cost of three billion francs, the Maginot Line became a World War 2 footnote and punch line when the Nazis simply did an end-run around the 200-mile barrier, through Belgium, on their blitzkrieg to Paris.

|

| Room with no view: an artist’s rendition of the Maginot Line |

I didn’t care. It was still a marvel of futuristic construction to my suburban imagination. I filled countless notebooks with improvised sketches for my own Maginot Lines. I drew whole cities tunnelled into the earth, filled with ant-bodied stick-men, bustling about, as I imagined adults must do, an underground utopia of perpetual motion.

Perhaps my Maginot mapping prepared me for my first year of university. I attended a school infamous for its own labyrinth of tunnels, which linked parking lots and classroom buildings and maintenance lairs, a heated escape from a never-ending winter above ground that often dipped to -30°C. It was rumoured that some grad students, as they shuttled vampirically from library to office to student residence, hadn’t seen the sun in months, even years. Perhaps, too, the distance between the orderly city of tunnels I’d crayoned onto my childhood drawing pads and the imperfect, often frustrating maze of this suburban low-grade university hinted at the gap that persists between the worlds that we manage to build and the ones we like to imagine.

Lewis Mumford, the renowned urban historian and social critic, called our city-making instinct the “will-to-utopia”. “It is our utopias that make the world tolerable to us,” he wrote, in his book The Story of Utopias, (published in 1922, just over a decade after the first kibbutz). “The cities and mansions that people dream of are those in which they finally live.” In his historical overview of the phenomenon, Mumford distinguished several different species of utopia. Our childhood visions of alternate realities perhaps best fit what he called the “utopia of escape”: fantasy worlds into which the human imagination could insinuate and find temporary respite from the drudgery or even pain of daily life. A picture of a Caribbean beach tacked to a cubicle wall. A Disneyland of the mind. Or Disneyland itself—utopia as a pret-a-porter escape from reality, a return to innocence (and over-priced amusements).

As one of the first true urbanists, a scholar of the city and the rich cultures it spawned, Mumford was less interested in escapist fantasies (like my Maginot dreams) and more curious about what he called the “utopias of reconstruction”. Utopia as a blueprint for a better way of life. Utopia as the most ambitious social-engineering project possible. Utopia as a cure for the messiness of modern life—or ancient life, for that matter. He described the Utopia of Reconstruction as “a vision of a reconstituted environment which is better adapted to the nature and aims of the human beings who dwell within it than the actual one.”

To me, that sounds a lot like the first kibbutz.

Apr 14, 2011

“How many Canadians does it take to change a light-bulb?” I was once asked by a German volunteer, while living on the kibbutz.

I shrugged my ignorance.

“Two,” he explained. “One to screw in the light-bulb, and the other to point and say, ‘Hey, did you know he’s a Canadian?’”

Even today, 22 years later, I cringe at the memory. The German jokester had hit the mark: Canadians pride ourselves on a lack of pride, a sense of humility in contrast to the chest-beating patriotism of our noisy neighbours to the south. But it’s a thin facade, a defense mechanism that hides a more general anxiety about who we really are as a people, as a country. As the recent Winter Olympics proved, or the maple-leaf stitched into backpack of nearly every young Canuck abroad, we still cling to the fragments of a evanescent national identity.

And as my German friend knew, that nervous tic often manifests itself, when amongst foreign travellers, in the odd parlour game known as “Did You Know They’re Canadian?” On the kibbutz, my next-door neighbour—one of several other token Canucks—played it often. When the subject of our country came up, he would cite the North of 49 heritage of various B-list North American celebrities and pop stars (this was the pre-Celine-Dion era) that his European interlocutors only had a vague recollection of: “Did you know that William Shatner is Canadian? And Michael J. Fox, too. And Bryan Adams and Wayne Gretzky.”

Such trivia rarely impressed the citizens of more established nations, cultures that had bestowed upon the world the likes of Shakespeare and Van Gogh, Beethoven and Chopin, Flaubert and Michaelangelo. When I first met Kurt, a longtime volunteer and a social worker from Vienna, I promptly exposed my superficial knowledge of his country: “Austria—just like Arnold Schwartzenegger!” His smile dropped. “He’s not Austrian,” came the reply. “He’s American.” He clearly didn’t indulge in the “Did You Know They’re Austrian” version of the game.

That joke came back to me again this week in the wake of Israel’s “Bieber-Gate”. The news: Justin Bieber, now the world’s most-famous Canadian (whether anyone over the age of 16 is willing to admit it), has been visiting Israel for a concert. The event, in itself, is a point of controversy. Every major artist booked to perform in Israel gets targeted by the Boycotts, Divestment, Sanctions movement, which encourages performers not to play, as a protest of the ongoing occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Some like Elvis Costello back out; some, like his Canadian wife Diana Krall, still come. And others, like Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, are forced into a compromise—in his case, playing on the “neutral grounds” of Neve-Shalom and later touring (and condemning) the “separation fence” constructed between Israel proper and the West Bank.

Needless to say, bubble-gum pop Christian teeny-bop crooner (and recent memoirist) J-Bieb isn’t the most political musician out there. But he still got drawn into the quagmire of Mid-East debate when he was invited to meet with Israeli P.M. Benyamin Netanyahu (known in Israel as “Bibi”), and then (according to some reports) balked when the P.M.’s office arranged for young Justin to meet with Israeli kids who lived in towns under assault by rockets and mortars from Gaza. Amid the P.R. fallout, various versions of events emerged: Bieber (or more likely his many handlers) didn’t want his tour politicized; the meeting was never a done deal; he was just over-extended from paparazzi harassment; he had already invited kids from rocket-targeted Sderot to his show; etc..

Amid the recent violence and unrest in Israel, Bieber-Gate was a relatively brief and harmless media tempest. Nobody has been injured, not even by the ravenous hordes of young Bieb groupies trailing his tour as though he were the Messiah. But it was a reminder that, in Israel, everything is political.

And as several online commenters pointed out, amid the typical tit-for-tat flame wars about the political stalemate in Israel/Palestine: “Did you know Justin Bieber is Canadian?”

That’s a light-bulb I’d prefer we’d keep dimmed.

Apr 8, 2011

It’s hard to do any reading about the kibbutz movement without coming across mentions of Rachel Bluwstein Sela. Rachel (known now simply as Rachel the Poetess or just Ra’hel) was the tragic-romantic heroine of socialist Zionism, a sort of Sylvia Plath of pre-State Israel, what one biographer called the “femme fatale” of the early kibbutz movement.

Like many of the socialist pioneers, she was born in Russia—the 11th daughter of well-to-do parents—and only visited Palestine, in 1909, on what was meant to be a tourist stopover with her sister on their way to study art and philosophy in Italy. The spirit of Zionism swept both young women up, however, and they stayed to work the orchards in Rehovot, south of the newly founded settlement of Tel Aviv. She was likewise enchanted by the old Arab town of Jaffa, and travelled to the various Jewish settlements carved out by the recent wave of young socialists, such as Chana Meisel, a new friend who encouraged Rachel to join one of these nascent communities.

Rachel headed north, to the Sea of Galilee, to live and study at the small women’s agriculture school at Kvutsat Kinneret. There, she fell under the influence of A.D. Gordon, the middle-aged philosopher-savant who captivated young protegés with sermons about the “religion of labour” and by the example of his own tireless work ethic. Rachel, who had penned verse since the age of 15, began writing in Hebrew, with a dictionary at her side, and dedicated her first Hebrew poem to her mentor. She tried to sublimate her artistic temperament and upper-middle-class upbringing through the arduous chores of her new community and becoming one of the kibbutz’s hardest workers. She would forgo art and music to instead “paint with the soil and play with the hoe”. These long days would become ever-more tinted in nostalgia when she looked back to Galilee toward the end of her too-short life.

With A.D. Gordon’s blessing, she left Israel in 1913 to study agriculture in Toulouse, France. However, the outbreak of the Great War separated her from her one true love—the land of Palestine—and instead she returned to Russia, where she tutored Jewish refugees and likely caught the tuberculosis that would shorten her life. In 1919, after the armistice, she joined other Jewish immigrants aboard the Ruslan and arrived back in Palestine. She settled in Degania Aleph, the first kibbutz, not far from the Kinneret agricultural school. But she never recaptured the joys of her first years of pioneering. Her disease soon manifested itself. Her TB-ravaged body was no longer suited for outdoor toil. And she couldn’t safely oversee the community’s children. She was compelled to leave—like Eve cast out of Eden, alone, unwanted.

|

| Rachel the Poetess (second from right) |

She despised cities but lived, for the rest of her days, in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, pouring her dwindling energies into her writing—deeply-felt poetry layered with a longing for the past, for a lost connection with the land of the Galilee, and at times at an Emily Dickinson-like vision and acceptance of her last days. She had relationships with different men, including one future president of Israel, but never married. She died in a sanatorium, alone, at the age of 40, in 1931. Ever since her body was buried at Kvutzat Kinneret, her reputation has only grown as a tragic icon and as a poet, whose simple Hebrew lyrics have been put endlessly to music. (Next year, she will be further immortalized, ironically perhaps, on the 50-shekel bank note.) Her short poem “My Land” best exemplifies her romantic spirit—one that defined the early pioneer movement, and a lens of nostalgia that’s hard not gaze through when one looks back upon the early history of the kibbutz movement.

Land of mine,

I have never sung to you

Nor glorified your name

with heroic deeds

or the spoils of battle.

All I have done

Is plant a tree

On the silent shores

Of Jordan,

And my feet

have trodden a path

Across the fields.

Mar 23, 2011

A few nights ago, I watched a

DVD I’d ordered, released in 2008 by a Greek production company, that profiled author

Amos Oz. It’s a fascinating complement to Oz’s

memoir, one that offers insight into both his creative process as well as his thoughts about the historical and even future importance of the kibbutz ideal.

|

| Amos Oz at work: black pen or blue pen? |

As a writer, I enjoyed the chance to hear the famous novelist talk about his working rituals. How he wakes early and goes for a brisk half-hour walk in the desert, near his home in

Arad, around 5 or 5:30 am, before settling down at his basement desk to write, in longhand, until noon or one. Then, after lunch and a siesta, he explained, “I come back and destroy what I’ve done before.” To maintain the flow of his process, though, he tries to end each writing day in the middle of a sentence, which he can then complete and continue the next morning.

“I am a domestic writer,” said Oz, one who is interested in exploring the family—”the most mysterious institution in the world.” “I don’t begin a novel with an idea,” he continued. “I begin a novel with a character. I hear voices. … The first sentence is the most difficult. Where does the story begin?… It’s like beginning relationship with a total stranger.”

He keeps two pens on his desk. One is black; the other, blue. “One is to tell the government to go to hell,” he said, with a smile. The other—the blue, I have to assume—he reserves for his storytelling, with its ambiguities and ambivalence, without the rhetorical certainty of his political prose. Those two sides of the writer, he feels, need to be separated. Still, his novels may serve a social good, even if that’s not why they are explicitly written. “We learn about the internal life of the Other,” said Oz about the function of literature. “And [through reading] there is a certain chance that we might become better neighbours.”

Late in the documentary, he offered a humorous summary of his 32 years as a member of

Kibbutz Hulda. How he had rebelled against his conservative father, at the age of 15, by running away to the kibbutz. How—speaking the elevated language of a boy raised in the city by polyglot Europhiles—he came across as a”funny bird” to the more rough-hewn kibbutzniks.

“I had a tough time integrating with the local society,” he recalled, “because they were tough farm boys and beautiful farm girls.”

How, as he began his career as a young writer in his 20s, he asked the kibbutz for a day, free from the work rotation, to focus on his creative output. How the membership had to debate this proposal in the general assembly and finally vote yes or no. (To their credit, the kibbutzniks granted Oz his day of writing—and then more time as his reputation and sales grew.) How, once he became a source of revenue as an author, the kibbutz authorities even offered him the help of two elderly members “to increase production”, as though his novels and stories were like factory widgets that could be manufactured with greater economies of scale. How, when he needed seclusion to finish a book, he would simply make a request to the kibbutz secretary and be granted money to pay for a quiet hotel room away from the community. And how, once he had to relocate from the kibbutz to Arad because of his youngest son’s severe asthma, he “lost that sense of a big family.”

It’s significant, I think, that the documentary ends with a long monologue from Oz, narrated over a silhouette of the author walking through the last light of a desert dusk, about the fall and rise of the kibbutz:

“The kibbutz movement is in a big crisis. Part of this is an external crisis resulting from the fact that socialism is not popular anywhere in the world. I believe for some people there will always be an attraction in a way of life that is like an extended family, where people share everything, where people carry the highest degree of mutual responsibility. In terms of human experience, for me, as an individual, as a writer, it’s like the best university I ever attended. I hope and believe that the kibbutz will have a revival… Maybe in another time. Maybe in a different country. We live now in a world where people work harder than they should work, in order to make more money than they need, in order to buy things they don’t really want, in order to impress people they don’t really like. This leads to a certain reaction, and this reaction will bring back some kind of voluntary collective experience.”

Mar 16, 2011

Last summer, I bought two paperback translations of works by Amos Oz from an independent bookstore/coffeeshop in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square. One was Where the Jackals Howl, a thin volume of stories, which I devoured over the final few weeks of my trip. The second was larger and more recent: Oz’s 500-page memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness. It’s not a book to idly skim through at the beach. Rather, it’s a masterly act of reconstructed memory, both haunting and humorous, a mental reckoning by the author of his family history and his own childhood in Jerusalem on either side of the War of 1948 and the turbulent birth of the State of Israel. The dark heart of the book, which Oz foreshadows and then deftly circles until the revelation of the final few sentences, is the crippling spell of depression that gripped his mother, that drew her away from husband and child, and that ultimately led to her suicide when he was 12.

Oz is known, of course, as both a world-famous author and a kibbutznik—or rather, ex-kibbutznik. He wasn’t kibbutz-born, wasn’t a “child of the dream”. Rather, he ran away to join Kibbutz Hulda, not far from the Latrun Monastery, after his mother’s death. It was in many ways a rejection of the right-wing scholarly nationalism of his father, uncle and grandfather. (He even went so far as to replace his surname “Klausner” with “Oz”: ”strength” in Hebrew.) He lived and worked and wrote and married and raised a family there for 30 years. He only left when his youngest son developed asthma, and doctors recommended a drier climate, so they relocated to the development town of Arad, near the Dead Sea.

A Tale of Love and Darkness doesn’t detail much of Oz’s kibbutz years, but it does offer fascinating glimpses, from this literary giant’s perspective, of how these communities were viewed in Israel at mid-century. He describes using matchsticks and other tidbits to construct imaginary kibbutz settlements as a child. He offers a comic anecdote about how he wrote a rebuttal to a newspaper editorial by founding prime minister David Ben Gurion—and how his entire kibbutz was angered at first by his presumption, until Ben Gurion writes a reply to Oz’s rebuttal and later invites him for coffee. He writes about how his father, who tried to convince him against joining a kibbutz, visits for the first time and is so concerned about fitting in and not offending his hosts that he arrives, not in his usual suit and tie, but in the rough work garb of a pioneer. He also describes the contempt in which the kibbutzniks were held by his grandfather and his nationalistic friends:

“As for the kibbutzim, from here they looked like dangerous Bolshevik cells that were anarcho-nihilist to boot, permissive, spreading licentiousness and debasing everything the nation held sacred, parasites who fattened themselves at the public expense and spongers who robbed the nation’s land—not a little of what was later to be said against the kibbutzim by their enemies from among radical Middle Eastern Jews was already ‘known for a fact’, in those years, to visitors to my grandparents’ home in Jerusalem.”

Oz’s memoir was a huge literary event in Israel when it was released, and in 2004, to coincide with the publication of this English translation, David Remnick profiled Oz in The New Yorker. At one point, they visit Kibbutz Hulda together and Oz reflects on his early years there:

“Tel Aviv was not radical enough—only the kibbutz was radical enough,” he said. “The joke of it is that what I found at the kibbutz was the same Jewish shtetl, milking cows and talking about Kropotkin at the same time and disagreeing about Trotsky in a Talmudic way, picking apples and having a fierce disagreement about Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. It was a bit of a nightmare. Every morning you would wake up and you were in the same place! I was a disaster as a laborer. I became the joke of the kibbutz.”

Oz’s memoir, like all his writing, is wrapped in this style of wry detachment and humourous retrospection. To Remnick, he describes his earliest years on Kibbutz Hulda as “a teen-age ‘Lord of the Flies,’ with better weather and a sensual permissiveness.” The author leads his guest around the quiet grounds of Kibbutz Hulda. Workers are in the fields. Many of the older buildings lie abandoned, as a generation of kibbutz children have not returned to their communal home. Yet, despite the decline of the movement, Oz still sees a remnant of the kibbutz philosophy, which he defended for so many years, still underpinning much of his nation:

“In a sense, the kibbutz left some of its genes in the entire Israeli civilization, even people who never lived on a kibbutz and rejected the kibbutz idea,” Oz said. “You look at the West Bank settlers—not my favorite people, as you can imagine. You will see kibbutz genes in their conduct and even their outward appearance. If you see the directness of Israelis, the almost latent anarchism, the skepticism, the lack of an in-built class hierarchy between the taxi-driver and the passenger—all of those are very much the kibbutz legacy, and it’s a good legacy. So, in a strange way, the kibbutz, like some bygone stars, still provides us with light long after it’s been extinguished.”