Feb 15, 2010

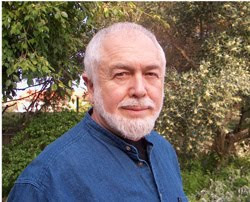

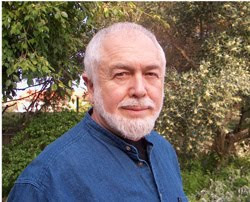

I got some good news over the weekend when an email arrived with news that my proposal for a talk had been selected by the organizers of the International Communal Studies Association conference, to be held late next June in Israel. My presentation will be titled “Representing Change on the Israeli Kibbutz” and will discuss how the controversial evolution of the kibbutz movement has been depicted by filmmakers from different perspectives.

I’ve already watched four recent kibbutz movies—three documentaries and one fictional comedy-drama—and I plan to order two more recent docs and view them before the conference. Coincidentally, the producers of one of these films, titled Keeping the Kibbutz, have just launched a new website to promote their film, as they complete post-production. It includes a trailer that gives a sneak peek of some of the kibbutzniks and their experiences.

I’m especially intrigued by Keeping the Kibbutz, as it centers on Kfar Giladi, a community on the opposite side of the Huleh Valley from Shamir. The footage and still photos from the film capture the beauty of the hilly landscape. One of the filmmakers was born on the kibbutz (his mother was a kibbutzniks, his father a Welsh volunteer) but moved to the U.S. when he was three. The film documents his return to the kibbutz and the gulf that now exists between the utopia his parents described and the privatized arrangements of the 21st-century community. Judging by the trailer, it has a great soundtrack, too. Congrats to all involved at Eidolon Films for nearing the end of this project.

I especially liked the description of their filmmaking philosophy on their website: “Eidolon Films specializes in character-driven documentaries that inspire, engage and inform. The individuals and communities we film are not simply subjects, but collaborators in the telling of their stories.” That should be the motto of literary journalists and creative nonfiction writers as well.

Feb 9, 2010

While academic studies have tracked the extent of changes on Israel’s kibbutzim over the past 20 years, for the best window into how those changes have been debated and how they have affected the lives of individual kibbutzniks, I’ve turned to documentary film. Over the past decade, a new sub-genre of Israeli filmmaking could earn the label “privatization cinema”—mostly documentaries, but also some fascinating fictional work, too. I’ve watched four already, and am looking forward to the upcoming release of a fifth. Each offers a different perspective and has helped me triangulate the emotional nuances of changing life in these communities.

One of the first I saw was HaZorea, a documentary produced and directed by Ulrike Pfaff, a former volunteer from Germany (now studying to be a police detective), who did several tours of duty on the kibbutz of that name. (Curiously, I discovered that linguist/political critic Noam Chomsky also spent a month on Kibbutz HaZorea with his wife in 1953; he is a controversial Jewish critic of Israeli foreign policy but retains fond memories of kibbutz life.) Pfaff returned to HaZorea for two weeks in September 2007 to film 50 hours of interviews and footage with a crew of three and a budget of about $25,000.

I watched the film three times as I prepared to give a post-screening talk about Pfaff’s documentary and the general changes to the kibbutz movement at the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival last November. The film offers what feels like an objective glimpse at the lives of the kibbutzniks at the time and some of the anxiety around potential changes to the lifestyle of the kibbutz. (HaZorea was still a traditionally communal kibbutz but in the midst of debating and voting on privatization measures; the documentary ends with the results of that vote—SPOILER ALERT!—in which the changes are not approved.) There is a slow-paced, casual atmosphere to the movie as a whole that reflects the languorous mood so typical (and so attractive) of kibbutz life and so at odds with the speed-tweaking pace of a city like Tel Aviv.

While Pfaff includes interviews with many kibbutzniks, young, old and middle-aged, two become the focus of the narrative: Hanna, one of the German-speaking pioneers who founded HaZorea, and Oriel, a “son of the kibbutz” who now lives in Tel Aviv and has returned to decide whether or not to become a member. (Pfaff actually returned to Israel to film two days of footage and interviews with Oriel, once she heard of his situation, because he was the perfect vehicle for the documentary’s drama—a kibbutz sitting on the fence between past and future.) “The kibbutz is a paradise for children and old people,” Oriel says, reflecting nostalgically about his freedom growing up in HaZorea’s “society of children”. “And for dogs!” quips Ran, a friend who still lives on the kibbutz (and provides much of the movie’s comic relief).

But the young adults and the middle-aged couples (and even, more reluctantly, the older residents) in the movie all seem to want changes to the communal rules that have guided their lives. When I spoke to Pfaff via Skype, she admitted that her own main criticism of the movie was a failure to find and interview those kibbutzniks—who remain in the majority—who don’t want changes to their community. She also admitted that while reaction to the film has largely been positive, criticisms have come from both ends of the spectrum.

“I don’t know if it’s possible to make a really objective film because in the end I can decide by editing what I want to put and what I don’t,” she told me. “There are other people that didn’t think it’s objective. [One viewer] was very, very mad at me about this movie. He said that I did it too negative and not objective. And there was another girl, born on the kibbutz, and she said it was too romantic and too positive about everything. So I think probably it is not possible to do it objective.”

Still, whether objective or not, HaZorea does a wonderful job of capturing both the pioneering spirit of the kibbutz founders, the charms and frustrations of one community’s current incarnation, and the uncertainty faced by the young people who will lead Hazorea into the future.

Feb 2, 2010

When I start talking about my writing project, I’m often asked “What is a kibbutz?” It’s a tricky question to answer. There is a specific definition of the kibbutz as a communal agricultural settlement founded by secular Jewish immigrants to Palestine in the early 20th century. There is also the more flexible legal definition established in 2004 by the Ben Rafael Committee in Israel to distinguish between traditional, privatized and urban communal arrangements of differing degrees of income redistribution and mutual reliance.

And then there is “kibbutz” as a sort of floating signifier, a word and a concept that often acquires different meanings from the different people who use it and the different communities who have been inspired by (and then adapted) the vision of the original settlements. I track “kibbutz” as a term using Google Alerts, and it’s fascinating to discover the strange new contexts in which the word arises.

Take the Ravenna Kibbutz in Seattle, for instance. It’s not a socialist experiment in the same was as the original kibbutz. Instead, it’s an intriguing group of young Jews living together in a co-housing arrangement in the Pacific Northwest. (I’ve heard of similar groups in Brooklyn, Portland, and Toronto.) I love their tagline: Would it kill you to find a nice Jewish commune?

There is Kibbutz Lubner, in South Africa, which uses the kibbutz-style collective model to create a community of caring for intellectually disabled adults. A factory and a farm allow them to find fulfilling work in a communal environment. Also in South Africa, an apocalyptically minded religious prophet has dreamed of a global chain of “whites-only kibbutzim” (missing the irony of a racist settlement inspired by a Jewish commune) but recently ran into trouble with the law.

Even before the disastrous earthquake in Haiti, some observers of this long-suffering nation were suggesting that Haitians look to the kibbutz for inspiration to revive their economy at a grassroots level. After the disaster, the kibbutz may offer a way to rebuild together. Haitians already have many forms of co-operative economy, such as the kombit, which could be adapted to the communal model of the traditional kibbutz, as one commentator noted:

Now is the time to bring the kibbutz model to Haiti or at least a kibbutz with some Haitian flavor. Just as [novelist] Jacques Roumain romanticized the kombit as the ultimate cooperative labor, Haiti should amalgamate the two and call her version a kombutz. … A kombutz can grow fruits and vegetables; raise cattle for beef and dairy; goats, chickens for meat and eggs; turkeys big enough to feed a village, and creole pigs. It can grow sugar cane, tree saplings for reforestation, or jatropha for biodiesel to power its own generators

Back in Israel, there is Kibbutz Givat Menachem—not actually a kibbutz, but rather another of the roughshod illegal outposts that right-wing settlers keep erecting in the occupied West Bank. This time, they used the term “kibbutz” to point out that many kibbutzim have also been built upon once-occupied Arab lands. The Israeli Civil Administration didn’t bite and replied, “This is a cynical attempt to build illegally by using the term ‘kibbutz’.”

Some uses of kibbutz are cynical. Others are inspired. (If readers know of any others, please email me.) What’s clear is that the word and the concept still carry great currency in Israel and around the world.

Feb 1, 2010

While not directly kibbutz-related, there was an interesting article by Saleem Ali about a proposed “peace park” along the Syria-Israel border, in the Golan Heights, not far from Kibbutz Shamir (which once was on the border with Syria before the Six Day War). The posting discussed a symposium last month in Tel Aviv about how ecological projects can help peace-building in the Middle East.

The Golan Heights are an especially complicated piece of land, even by Mideast standards. Formerly part of Syria, captured by the IDF in 1967, and populated largely by Druze Arabs who don’t consider themselves Muslim or Palestinian or Israeli and practise a highly secretive splinter sect of Islam. (Confused yet?) What I most remember about visiting the Golan Heights when I lived in Israel 20 years ago was the Shouting Fence. Located near Majdal Shams, one of the major Druze villages on the slopes of Mt. Hermon, this barbed-wire no-man’s land had separated friends and family members since 1967. For years, they had come (usually on Fridays, I believe) to communicate via megaphone or loud voice to other Druze across the new border in Syria.

I’m not sure if the Shouting Fence still exists in that form, but it was strikingly symbolic of the complex and sorrowful divisions in this part of the world. (I wrote a poem with that title years ago and have been tempted to call other projects by that name.) That’s why the idea of a borderland peace park holds such hope (even if many critics consider it mere dreaming), especially for the Druze people, who have never really cared much for the national borders that divide them.

In his article / blog entry, Ali, the author of a book about peace parks, did mention (although didn’t name) a kibbutz in the Jordan Valley that has a special arrangement to grow crops on the Jordanian side of the border and a “peace island” in that region, where Israelis and Jordanians can visit without visas. He also acknowledged skpeticism on both sides of the debate, noting that “Arabs are highly suspicious of conservation efforts in this context just as Native Americans have been suspicious of the US. National Park system, whose establishment often excluded them from their land. Thus any peace park must be one where access and economic development are concurrent with conservation.”

Still, I find it hopeful that the idea of ecological conservation might be used as a tool to get two deeply divided nations talking about peace and, more importantly, to get deeply suspicious peoples meeting each other on common ground.

Jan 26, 2010

I only vaguely realized at the time how lucky I was to land at Kibbutz Shamir. During my months there, I heard rumours about the long days, rough conditions and general dissatisfaction of volunteers at other, less well-off kibbutzim. In 1988/89, when I lived in Israel, the whole movement was undergoing a profound financial crisis. The nation had emerged from several years of recession and hyper-inflation, and many kibbutzim were saddled with huge, oppressive debts. Cutbacks were necessary. Standards of living plummeted. Many members lost confidence in the movement, in their kibbutz, and left for Israel’s cities or immigrated overseas. Numerous kibbutzim struggled in this tailspin of economic, demographic and ideological decline.

Shamir wasn’t one of them. As volunteers, we were treated well. The kibbutz organized Hebrew lessons, educational sessions, and took us on Shabbat day trips and, twice a year, an extended five-day trip down to the Gulf of Aqaba and back. We were buffered from the economic anxiety experienced on many other communities. When I returned last June, I had the opportunity to interview Itzhik Kahana, who had been in charge of the orchards when I was a volunteer and is now serving as the kibbutz director. I include here an exercpted transcript of our talk about the past, present and future of Kibbutz Shamir.

What is the story of Shamir?

It was founded in December 1944 by the group Hashomer Hatzair from Romania. Most of the people were from two groups, of different ages, but the same movement. They knew each other well. They came to Israel and started building the kibbutz near Haifa. Gathering there, not building a kibbutz. They were in the port and in factories for about five years from 1939 until they were assigned to this spot because the other spot was not frontier enough. The movement gave them a few options and eventually they chose this one because there was completely nothing except rocks. That seemed to appeal to their frontier mentality.

How many people were in that first group?

About 160 people. About 40 to 50 left quite early. It was very harsh in the first few years. Other people joined the kibbutz, like my mother, who came out of Romania after the war, after she was in a British prison for six months for illegal immigration. After she got out—after she was sent here—then she met my father.

Was this the time of the “tower and stockade” movement?

A bit later. This land was bought by the Jewish National Fund. The main areas of farming in the beginning was on this hill, which is not much. For the first five years, they just took out stones out of the fields. There were fields for livestock, but the standard of living was very low. Nineteen-forty-eight made a big difference because all the Arabs of the valley left the villages and went to the mountains to wait for the Syrian army to kick out the Jews, which didn’t happen, so we got fields in the valley. All our agriculture is in the valley. The field-growing is in the valley.

On the Arab fields?

No. Some of them were fields, some of them were swamps we couldn’t use. Whatever they could use, they’d use. There was a lot of digging of canals. We had to spend a lot to make this land arable, so you could work on it. … We were living on agriculture basically until the beginning of the 1970s.

The post 1948 border [with Syria] must have added another level of tension.

Some people left because of it. It was too much for them. There used to be shooting almost daily. Just random. Sometimes it was more—mortars. That’s one of my first memories, the shooting.

In 1972 we opened the optical factory. The idea is to get work for the peple that are getting older and can no longer work in agriculture and it went on like this for about 10 years. It was bifocal lens. Then, at that time, the group that led the optical factory decided they needed something more sophisticated and decided to develop multi-focal lenses. It wasn’t easy. It took 10 [more] years.

So by the beginning of the ‘80s, there still was nothing there. We invested money into new technologies that we bought, in ’83, and then we bought another line, and another, and another. In the early ‘90s we finally had a breakthrough in the production of the multi-focal lenses. It’s climbing up.

But you’re still doing agriculture?

In the ‘90s, it started to go down as a main source of income and a main source of jobs.

And until the ‘90s?

There was a lot of people working there.

In the orchards?

Orchards, fish ponds. We tried almost everything. Cattle, sheep, pigs.

What was more successful?

The pigs were successful. But in 1963 the Knesset passed a law that Jews are not allowed to raise pigs, so we had to close it. The beef is very successful. It’s run by professionals who do it right, out of tradition.

In 1999 we accepted an investor in the optical factory. … Then, we got a partner in Shalag [fabric-making factory], which is a group of investors. That was the basic idea—that we go to public offering to capitalize on our success.

To raise money?

Basically, but first the money goes to the partners. Then it went to two things: the pension fund for the members, which was almost empty, and [our debt], which was very heavy and very annoying.

Was this a result of ‘80s financial crisis?

No, we just lived beyond our means. We didn’t run our financial things right.

Do you still run a volunteer program?

No. Farming went down… We now use a lot of Thai workers. The margin of profits is much lower and you cannot support volunteers in the system. Kibbutz members need all the jobs. Someone can work in the dining room for income. Before, it was a volunteer job.

Has the ideological vision of kibbutz movement changed? Are kibbutzniks still leaders in Israel?

Unfortunately not. We are one of the most hated groups in the country. We are not leading anymore, like it was in the army, in government, and we don’t have the pretenses to lead. We tried to. Whoever wants to be a politician goes into politics. Now we try to be successful in what we do, and eventually that helps you to lead. … The country is built; we don’t have to rebuild it. We have to find new challenges.

Jan 26, 2010

I stumbled across another academic paper, published in 2004, by the same authors, Richard Sosis and Bradley Ruffle, and based on their “100-shekel” field experiments. In “Ideology, Religion and The Evolution of Cooperation,” Sosis and Ruffle differentiate not just between kibbutzniks and city dwellers, but also between religious and non-religious kibbutzniks. “The emergence and stability of cooperation,” the authors write in the first line of their paper, “has been a central theoretical problem for those who study human social behaviour.” So, not Why can’t we get along? But rather, Why—given an apparent evolutionary impulse to look out for our own interests first—do we (or at least some of us) bother to cooperate at all?

Biologists have worked out explanations like “kin selection” to explain away cooperation within the me-first theory of natural selection. But Sosis and Ruffle focus on a variable unique to the human species: ideology. How does what we believe affect how we behave? And in the context of the Israeli kibbutz, does this effect vary between the secular kibbutzim that form the bulk of the movement and the smaller number of religion-minded communities? Did the deity make us do it?

What they discovered, based on who took out the fewest amount of shekels from the “common purse”, was that male kibbutzniks who regularly attended synagogue, where they perform public rituals, were most “cooperative”—or at least most committed to the sharing philosophy of the kibbutz. It makes sense. The cooperative communities that have endured the longest since the 19th century have been religious communes. But with religious kibbutzim (which tend not to be ultra-Orthodox), there isn’t the same pressure to stay on the community; you have the choice to leave if you want. It’s an interesting conclusion and poses challenges to secular communities who hope to cultivate the cooperative impulse in their members—and in future generations.

Even the many secular rituals of the non-religious kibbutzim—the shared Shabbat dinner, the public holiday celebrations and entertainments, the collective debates of the general assembly—don’t inspire the same sense of communal fraternity as sacred, supernatural, religious acts. As the authors write, “the bonds forged through a common secular ideological belief, even when supported by ritual activity, do not appear to create the long-term trust and commitment achieved within religious communities.”

I grew up Catholic, but shed most of those religious beliefs (thanks largely to biology class) by the time I reached university. And yet likely the most communal, cooperative activity I participated in (aside from the kibbutz) or at least witnessed was the volunteer work and church socializing my parents were involved in. I remain agnostic, borderline atheist—and too often disconnected from the community around me. Despite my secular beliefs, I can’t dismiss outright the religious impulse and even (despite its blood-soaked history of repression) the Catholic (or any other) church.

Ultimately, I hope that some other, less-toxic, less-supernatural, more-earthbound ideology might bind us together. (Perhaps the “eco-spirituality” that has pissed off the Vatican in James Cameron’s Avatar—and that is at the core of the eco-village movement, which has inspired several kibbutzim in Israel, too.) But Sosis and Ruffle’s research suggests that secular ideology—even wedded with Kumbaya-ish, treehugging, circle-dancing group-building rituals (been there, hugged that)—won’t lead us away from our own ingrained self-interest as much as a belief (or perhaps a fear) of a Higher Power keeping track of how many shekels we take from the collective envelope.

Jan 19, 2010

I’ve been enjoying my new tenure as a research fellow, for the next six months, at the Centre for Co-operative and Community-Based Economy (formerly, the B.C. Institute of Co-operative Studies). Every Friday, at 10 am, the staff, my fellow fellows and anyone else interested in what goes on here gathers for tea and conversation. (If you’re on campus, you ought to come by!) On a recent Friday, talk turned to the intriguing results of the socio-economic experimental “game” called “Ultimatum”.

In Ultimatum, two players must decide how to divide a sum of money (say, $100). The first person makes an offer; the second person can either accept or reject that offer, but if he or she rejects it, both players get nothing. It’s a one-offer deal. There is no negotiating.

The rational response of Player #2 should be to take whatever is offered by Player #1—it’s better than squat. However, in practice, many players will reject offers of 30% or less. Why they would take nothing rather than a little is one question. Why Player #1 is such a Scrooge is another—although, at least in pure economic science, players are acting “rationally” (i.e., in their own best interests) if they low-ball their compatriot, who has little leverage beyond accepting or rejecting the offer. Further studies have shown variations based on culture and gender: women behave more cooperatively, apparently, and are more likely to propose an even split.

Later, I came across a brief article in the New York Times Magazine annual Ideas issue that described a “drunken Ultimatum” experiment, in which imbibers at a bar were asked to play. They were even less likely to take anything less than a 50:50 split, suggesting that short-term revenge (or a sense of injustice) rather than long-term strategizing was behind this seemingly irrational behaviour.

Of course, after learning about Ultimatum, I immediately wondered: W.W.K.D.? What would a kibbutznik do?

I wasn’t surprised to learn that someone had already answered this question. Because of its unique communal set-up and voluntary membership, the kibbutz is one of the most intensely studied communities in the world, generating thousands of academic studies over the years. (I can only imagine what it must be like to be kibbutz-born identical twins, one raised there and one raised elsewhere—you’d be the ideal choice for every social science, nature-vs.-nurture experiment on the planet!)

While they didn’t use Ultimatum, Bradley Ruffle and Richard Sosis deployed a similar experiment to compare the level of co-operation of kibbutzniks (taken from relatively well-off, still-traditional kibbutzim) between fellow (but anonymous) kibbutz members versus “outsiders” (i.e., likely townsfolk). To simplify, the two players were told that an envelope held 100 shekels and they could take as much or as little as they wanted, but so could the other mystery player. If what the two players took totalled more than 100, then they would receive nothing. If it totalled less than 100, then what remained was multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally between the two players, plus they could keep whatever they had removed originally. The idea is to distinguish motives for individual gain (i.e., taking a lot and hoping your opponent takes a little) from those of collective gain (i.e., taking nothing or a little, knowing that what remains will be redistributed fairly with dividends).

The 2006 paper documents some surprising results. When faced off against another (unknown) kibbutz member, kibbutz subjects showed a willingness to behave cooperatively and only take a little from the envelope. When matched with an “outsider”, they behaved exactly as other subjects in the control group of non-kibbutzniks and were tempted to take more from the envelope. (Sociologists describe this as an example of “in-group bias”.) Equally intriguing, the longer that someone had lived at a kibbutz—i.e., if they were a born and raised kibbutznik versus a new member—the more likely they were to behave less rather than more cooperatively. New members—at least those who choose to join the still-traditional kibbutzim (the experiment was done in 2000, before the acceleration of privatization)—tend to be more ideological in their communalism than existing kibbutzniks.

As the co-authors write in their conclusion:

Despite the promise of a universally cooperative group, kibbutz members cooperate more with members of their own kibbutz than with city residents. What is more, when paired with one another, kibbutz members and city residents exhibit identical levels of cooperation. In this sense, kibbutz members may be said to be conditionally cooperative individuals. Our findings attest to the strength of the psychological foundations of in-group-out-group biases, in spite of a society’s efforts to train its members otherwise. Even members of this once idyllic, voluntary, cooperative community do not treat all individuals alike. Instead, they appear to form expectations concerning others’ degree of cooperation and reciprocate in kind.

Jan 19, 2010

|

All the past we leave behind;

|

|

|

We debouch upon a newer, mightier world, varied world,

|

|

|

Fresh and strong the world we seize, world of labor and the march, Pioneers! O pioneers!

—Walt Whitman, “Pioneers! O Pioneers!”

What must it have been like to be one of the founders of the kibbutz—to be a pioneer? That word carries such precious meaning in the history of Israel, of many nations. It invokes a sepia-tinted vision of the young people who uprooted from Europe to break the rough soil of Palestine, who dreamed not just of forging a new nation but a new way of living.

I’ve tried to imagine my way under their skins, into their minds, but the high walls of history, of language, of culture, of my own tidy 21st-century Canadian life, block the view. I suppose I’m a descendant of pioneers, too, a generation off the farm. Every summer, we made the pilgrimage—four days of relentless driving westward on the Trans-Canada—to my mother’s birthplace and her family’s wheat and canola fields near the Turtle Mountains of Manitoba. But the English and Belgian farmers who settled around Deloraine were hardly the same kind of dreamy ideologues that broke soil 100 years ago along the shores of the Sea of Galilee.

I’ve been reading excerpts from these pioneers’ early writings. The most famous book is a collection, translated as Our Community, taken from the communal journal of the 27 members of a youth group who lived for nine months at Beitania Eilit, atop a mountain overlooking the Sea of Galilee. They slept together, in tents, while working agricultural jobs until they could be assigned a community of their own. Their nights were filled with intense conversations about the destiny of their project, their fears and doubts, the sublimation of their desires for the larger goals of the group.

The words recorded in their communal journal are as angst-ridden as the secret diary of any hormonally flustered teenager sent away to summer camp. The emotional ups and downs are raw and manic, a gushing forth of innermost thoughts—what historian Henry Near describes as a “special, somewhat eccentric style of speech and thought.” (I can’t imagine the laconic farmers I knew from my summers in Manitoba ever subjecting each other to such Freudian analysis.)

I try to picture this group—23 men and four women—huddled around a campfire on a Galileean hill. To feel the exhaustion in their bodies after a long day’s work, plowing fields or building the road to Tiberias. To eavesdrop on their anguished group confessions, voices emerging from the shadows, competing visions of a new nation. In the words of one of the authors:

From the beginning our life was hard and bitter… [D]aily matters joined us together; however, each person in his own corner lived through the awful transition from idea to practice. … Erotic relationships were limited by the hardness of reality. Pointless matters filled the empty spaces between one person and another and silenced the soul’s cry with no hope of escape. The word “substance” became a fetish for everyone.

While these pioneers were secular socialists, fleeing in many cases from the religion of their parents and grandparents in the Old World, there was a quasi-spiritual dimension to many of their lengthy debates and discussions and philosophizing. Beitania, as another participant recalled, “was more like the solitary monastery of some religious sect, or an order with a charismatic leader and its own special symbols. Our ritual was that of public confession. … This was a rich mental feast, but also involved self-torture which served no purpose. … The individual was under the continuous scrutiny of the group, which was not afraid to show mental cruelty at times.”

And then one long night, as two Beitania members confronted each other before the group, these pioneers had a “breakthrough”—at least according to the record of “Our Community”—on what became known as the “Night of Atonement”. Hidden jealousies were confessed to. Secret desires revealed. The inequalities between the men and women acknowledged. “And from that night on,” the Beitania journal records, “the life of the group began.”

While I was at Shamir, there was a camaraderie amongst the volunteers, perhaps even a late-night confession or two. But there was nothing like the deeply felt emotional enterprise of these first pioneers, who had left their home countries and parents behind, likely never to be seen again, to journey to a rough new land amid an already existing population of Arab tenants who were at best skeptical of the young Jewish immigrants. The physical intensity of the work, the psychic intensity of the group—what one Beitanianite called its “social eroticism”—proved too much for many of these pioneers. Some abandoned the first attempts at settlement. Others committed suicide in despair. But out of their tears and frustrations grew the first shoots of the kibbutz movement—and the hardier myth of its pioneers.

|

Jan 18, 2010

If the dining room is the centre of communal life of the kibbutz—where gossip is traded over meals and decisions debated at general assemblies—then the volunteers’ bar (or “Volly Bar”) was the hub of volunteer life, for better or worse, during my tenure at Kibbutz Shamir. Every Friday evening, after Shabbat dinner, most of the foreign volunteers and a handful of the younger kibbutzniks would gather in the ramshackle cabin to drink too much and get to know each other. There was much craziness and camaraderie, but also some serious sharing and learning, too—at least for a kid from the suburbs of Ottawa, encountering for the first time people of my own age who were living through the geopolitical dramas of our age, rather than just reading about them in the newspaper. My first bar night on Shamir was a revelation.

Thurs. Oct. 27 [1988]

I don’t think I could begin in my awkward writings to do justice to the events of the last evening, but I must give it a try anyway.

I spent most of the night pulled up at a stool at the volunteers’ bar, quaffing “Goldstar” beers (only 60 agora for a pint—that’s about 2 pints for a Canadian dollar) and chatting with other volunteers. The beer was surprisingly good, relatively light tasting (I think it is 4.8% alcohol) but not like American piss-water beer.

Paul, a South African, and I exchanged stories on a number of topics and common interests including music (he likes Pink Floyd, The Doors, The Grateful Dead, Lynyrd Skynyrd among others as well as despising the throbbing disco music that is apparently played continuously at the bar), sports (he was interested about the Wayne Gretzky trade and how the Oilers were faring), politics (he knew a great deal about the upcoming American and Canadian elections), and travelling (he and a friend had spent 4 months driving across North America in a van).

The most fascinating conversation of the evening, I was just a mediator in. Ali, a young Arab living in an area of the Golan Heights captured from Syria by Israel during the Six Day War, and Paul took turns questioning each other and discussing the tense situations in their respective nations. Paul feels that change is a necessity in his homeland of South Africa, but a slow change, one that he says is already in process, not the violent revolution proposed by Nelson Mandela whom Ali said he respected greatly. Paul does however feel that Mandela should be released as he could cause more damage to the government by becoming a martyr in prison than he could as an old man with his freedom. Ali says, despite living in Israeli territory, he still considers himself a Syrian, though he doesn’t seem to harbour any resentment for the Israelis, as he works beside them, picking fruit for the kibbutz.

Jan 12, 2010

“Of all that happened in our time, only one thing will remain in our collective memory: the kibbutz. Not the yeshivas, nor the towns, nor the ‘build your own house’ neighborhoods, nor the shopping centers. All these, along with the materialism, privatization, property sales, exist all over the world and are of no interest to anyone. The kibbutz is the most original creation, not only in Israel, but in the whole twentieth century. It will become more and more significant as time passes.”

—Joshua Sobol, playwright, former resident of Kibbutz Shamir, and screenwriter of The Galilee Eskimos, quoted in an interview reprinted in Kibbutz Trends (Fall/Winter 1998)

Jan 12, 2010

On Tuesday, October 25, 1988, I arrived in Israel in a light-headed daze of dislocation, sleeplessness and culture shock. I can’t recall how long it took to travel by plane to Tel Aviv all told. I’m pretty sure we stopped in London, at Heathrow, before continuing on. I vaguely remember sitting between two large middle-aged men in the dark suits and brimmed hats of the ultra-Orthodox. One complained to a steward that his special-order meal, while labeled “kosher”, hadn’t been approved by his particular rabbi. I was starving and tempted to ask if I could eat the meal but pretty certain that definitely wouldn’t be kosher.

Once in Israel, I thought my luggage had been lost (I note this in my journal) but later located it, although I can’t recall the panic I must have felt. I do remember the abrupt shift in climate: I’d left amid an early snowstorm in Canada and arrived in (what felt to me) a sweltering heat wave in Tel Aviv. I recall lugging my backpack and duffel handbag (both with the requisite Canadian flags stitched across them by my mother) through the sliding doors of Ben Gurion airport, into a wall of heat and a clamorous throng of people. My eyes felt blurry. Signs were being thrust out, covered with words that I could almost but not quite read, like the bottom line on an optometrist’s exam. Then I clued in: Hebrew, of course. (Yes, I was either that naive or that out of it!)

Back in Canada, I’d arranged for a kibbutz stay and carried a letter of introduction, but I hadn’t been assigned to a specific community yet, so I had to journey into downtown Tel Aviv (by bus, taxi or sherut—I don’t recall) and locate the volunteer office. I remember a small, dimly lit room, and the coordinator indicating a map of Israel, the narrow geography of (to me) an unknown nation. Where would I like to go? he asked. The south, the north, or the centre?

We were in the centre of the country already, and I felt like I might perspire into a salty puddle if I had to step into the sun again. The south—into the Negev Desert—was definitely out of the question. I’d grown up in two of the coldest cities (Winnipeg and Ottawa) in one of the coldest nations in the world. I wasn’t built for the heat. I asked to head north.

The coordinator consulted his book, looked at the map, and then pointed north—far north—to Kibbutz Shamir. Before I could make out the dot, my eyes drifted farther up (but not that much farther) to the words “Lebanon” and “Syria”. I was hardly a Middle East expert, but I was news-wise enough to recognize that relations between Israel and its northern neighbours had been anything but cordial, especially since the Lebanon War of 1982. Still, I’d made my choice. I would head north, to what Israelis called “The Periphery”, nearly to the borderland slopes of Mt. Hermon.

When I found the central bus station, I realized that I was one of the few people (male or female) of my age (20 at the time) neither in uniform nor armed with an Uzi or an M-16. I think the only real gun I’d ever seen before was a Luger pistol owned by a great-uncle, a relic of the Second World War. Here, in Israel, weapons dangled as casually from shoulders like fashion accessories. I felt a little naked, and conspicuous, without one.

The bus ride took me to the town of Qiryat Shmona, and then another ride across the Huleh Valley to Shamir. By then, night had fallen, so I didn’t get a sense of the valley or the kibbutz. I had dinner in the dining room, met a few other volunteers, and then collapsed in my new room.

Reading my account of the next morning, my first on Shamir, stokes old memories. The landscape over which Shamir looks—the Huleh Valley, bisected by the Jordan River—remains a calming vista of lush farmland, orchards and irrigation ponds, although only a few years ago it was ground zero for Katyusha rockets launched by Hizbollah fighters in southern Lebanon. The sunset photo atop this blog was taken last June, just a few kilometres north and a little higher up the slopes from Shamir.

And there was a strangeness, too, to this rural landscape, with the mongoose (I’m still not sure of the plural!) that slipped between the cabins and the eerie shriek of the “rock rabbits” that lived on the embankments of the kibbutz and the keening howls of the wild dogs at dusk beyond the barbed-wire circumference.

It would take me a while to understand the perhaps unintended irony behind the reference to the volunteers’ neighbourhood, set apart from the kibbutzniks’ quarters (and now empty—Shamir hasn’t taken volunteers in several year), as The Ghetto. The name evokes the cramped shtetls and prejudice that Eastern European Jews hoped to escape by immigrating to Palestine and founding the agriculture-based kibbutz movement. It also suggests the doomed yet valiant uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto during the Holocaust—a story I would only learn later when I visited the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum outside of Jerusalem.

There was beauty in this land, especially for a kid from the cookie-cutter suburbs of Canada. But there was a darker story, too, that I was still too blinded by the novelty of my experiences to be able to read.

Jan 12, 2010

Wed. Oct. 26 [1988]

My first morning on the kibbutz [Shamir] and what a beautiful one it is! The view from outside my cabin of the hills of Galilee rising out of the mist is breathtaking.

I spent most of the last evening chatting with my next-door neighbour, a fellow Canadian as it turns out, though he’s been living in Europe the past 5 years, exchanging stories and learning about the different jobs he’s had to do on the kibbutz. I still can’t remember his name, he was one of the people introduced to me in the T.V. shack.

All last night I could hear the unnerving sound of mongoose (mongeese?) howling in the valley below, sounding disturbingly close at times. My bed seems comfortable enough; the sleep I got in it last night managed to work out the painful kinks in my backside brought on by lugging my massive backpack all over Tel Aviv.

It’s afternoon and I’m sitting on my porch, looking at the rest of the “Ghetto”, the affectionate moniker of the volunteers’ village. Tomorrow will be my first work day and God knows that I will be doing. I’m hoping that it will be nothing too industrial or mechanical such as the optical factory or the Shelagh [sp: Shalag].

I just saw my first mongoose, it slithered up to the porch of the T.V. cabin to pilfer some of the weiners left for the cat. They are very slimy looking creatures, long and slender with fine, light brown hair and a thin tail, straight as an arrow with a dark, pointed tip. They have a casual, undulating gait but are inclined to sudden dashes and leaps to pounce on food or at the slightest noise.

I was given a tour of the kibbutz by Ami, the volunteer leader, a short Jewish man with thinning blonde hair and obviously stricken with some ailment as he walks with an exaggerated gait, having to lift lift his foot up distinctly higher than normal for each step and thus usually travelling in a golf-cart-like vehicle.

He briefly explained to me the history of Israel in general and Kibbutz Shamir in particular, as well as outlining the geographic area surrounding the kibbutz. It lies right on the edge of the Golan Heights, adjacent to land only recently claimed by Israel in the Six Day War of 1967. Over the surrounding mountains lie the borders dividing Israel from Syria and Lebanon, only about 20 or 30 km away. In 1974, two kibbutzniks and a volunteer were killed here by terrorists. He seems to feel that if Israel is ever going to gain any lasting peace with its hostile Arab neighbours, it will have to give up some of the occupied territories. Most of the older men on the kibbutz would have fought in one or more of the six or seven “major” wars Israel has waged since its conception in 1948, actually struggled violently for the very land they now cultivate and build upon.

Jan 11, 2010

There was an informative news item in Ha-Aretz, one of Israel’s leading newspapers, about the state of the kibbutz movement as it celebrates its 100th anniversary. The article offers a clear summary plus supporting statistics of how many kibbutzim have voted to “privatize” and what that really means. (“Privatize” has a connotation in English that doesn’t capture exactly what’s happening in these communities, once run as anarcho-socialist communes—it makes it sound like they’re being sold off to McDonald’s or Procter-Gamble, which simply isn’t true.)

Most interesting, while the trend of the past 10 years has been toward increasing privatization, so that it once seemed that the death of communalism was inevitable in the movement, last year only five more kibbutzim voted to differentiate their salaries and loosen their communal arrangements. That still leaves 65 “traditional” communities and nine half-and-half “integrated” kibbutzim.

One commentator suggests that 2009 may mark the “peak” of privatization and a realization that moving from a cooperative economic model to a more market-driven one often only benefits a fraction of any community in the end. Dr. Shlomo Getz, the head of the Institute for the Study of the Kibbutz and the Communal Idea in Haifa, cautioned not to make too much of these numbers and assume that privatization has “stalled” — several more communities are considering, and will likely vote on, altering their economic structure.

Along with two American colleagues at the University of California (an idealistic institution suffering through its own financial crisis), Dr. Getz has been surveying kibbutzim for 20 years and documenting 50 types of changes that have been implemented. Dr. Getz is a member of Kibbutz Gadot — which privatized not long ago — and a hospitable exemplar of the kibbutz ideal. On my visit to Israel last summer, he took me under his wing, tutored me on the essential context of his research, introduced me to his colleagues at the institute, and even had me over for dinner with his wife when I stayed at Gadot.

As Dr. Getz reminded me during our interview, the kibbutz has never been a static phenomenon. It has always been an open, evolving society, unlike insular religious communes, which tend to coalesce around a hard kernel of unchanging faith or dogma. In the 1970s, industry and higher education became part of the agricultural kibbutz movement. In the 1980s, the sleeping arrangements in the children’s houses gave way to traditional parenting.

“But now, from the beginning of the 1990s,” Dr. Getz explained, “the change is total change—multi-system change. There are three or four crises at the same time. You have to make changes in different aspects at the same time.”

An anniversary, like 2010, makes a good opportunity to look back and reflect on where a community (or an individual) has come from, and what has been lost and found on the journey. So it will be interesting to see, if it’s true that the sense of crisis has largely passed and that many kibbutzim—both privatized and traditional—have found economic stability, whether the urge to privatize will continue or whether a nostalgia for the communal life of the near and distant past will once again come to the fore.

“This stage of the kibbutz, it’s not the final stage,” Dr. Getz told me. “It’s the new kibbutz now. In 20 years, it will be another one.”

Jan 6, 2010

One of the most courageous and insightful writers in Canada—anywhere, in fact—is Deborah Campbell. A graduate of UBC’s MFA Writing program, who also studied in Paris and Israel, she brings an investigative journalist’s tenacity for nailing down the facts, a literary author’s sense of story and character, and an activist’s willingness to speak truth to power. In recent features in The Walrus and Harper’s, she has told underreported stories about life in Iran and the plight of Iraqi refugees in Syria.

I recently read This Heated Place, her book about her return journey to Israel, researched in the fall of 2001—she was traveling through the country when the events of 9/11 hit—and released in 2002. It’s a compelling (if too short—I wanted each chapter to be at least a couple pages longer) tour of a troubled nation, then caught in the spiraling violence of the Second Intifada, with suicide bombings and Israeli Defence Force retributions. In the book, she moves from the anxiety of Israeli citizens to the utter despair of Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip.

Her chapters about Rabbi Riskin, a hardline settler in the West Bank, and the photographer who took the famous photo that rocked the world of a Palestinian father trying vainly to protect his son in a Gaza crossfire are especially moving and depressing.

She looks briefly at life in a kibbutz and the decline of the movement in a chapter titled “The End of Utopia”. In it, she visits Kibbutz Ma’agen Mikhael, north of Tel Aviv, a successful community that has maintained its communal arrangement, and draws on Daniel Gavron’s excellent book The Kibbutz: Awakening from Utopia for general context about the struggles of the movement.

As Campbell writes of the allure of the kibbutz:

The kibbutzim, once the lifeblood of the fledgling nation, are part of what inspired my original interest in Israel. I was enamoured of the images of self-sacrificing pioneers who devoted their lives to planting gardens in the desert … and of people who placed national service ahead of personal gain.

As she tours the kibbutz with a member, Campbell observes that the beit yeladim —the famous “children’s houses” where children were raised and slept communally, with their parents visiting them for a couple hours in the afternoons and evenings—were disbanded in 1981. “Now, some kibbutz members believe that the end of the children’s houses,” she writes, “signalled the beginning of the end for the movement.”

The pioneering spirit and energy of the secular, left-wing kibbutz movement has been supplanted, controversially, since 1967 and the Six Day War by religious, right-wing settlers, who have built and defended communities in the Occupied Territories—the source of much of the violence and tension in the region.

Campbell ends the chapter on a poignant note:

The kibbutzniks, once held in such esteem, are losing influence at a time when their presence is most needed. As I leave Ma’Agan Mikhael … it is with the knowledge that a proud chapter in the short history of modern Israel has all but ended.

Has this chapter truly ended? Many observers and kibbutzniks would agree that it has. But I’m curious how (and if) the spirit of the original pioneers continues to evolve and inspire other people in unexpected ways.

Jan 5, 2010

Last June, when I was visiting the Institute for the Study of the Kibbutz and the Cooperative Idea, at the University of Haifa, I was asked by one of the researchers there if I had a name for the book I was working on about the kibbutz movement.

“Look Back to Galilee,” I said.

“That sounds very Christian,” he replied.

I don’t think he meant anything negative by it—it was a simple observation, and an accurate one at that. What Israelis call Lake Kinneret, Christians know as the Sea of Galilee. And the “Man from Galilee” is pop-hymn shorthand for J.C. Himself.

I have my reasons for clinging to this title, even though I have an alternative name squirreled away in my back pocket. One is to acknowledge that the book (or whatever this project becomes) is hardly a 100% objective historical account of the kibbutz movement, but rather the perspective of one non-Jewish outsider who has a fascination with the subject of communal life in Israel.

The title seems fitting, too, for the memoir aspects of the writing—I do plan to “look back to Galilee” and recall my experiences and the people I met during my tenure at Kibbutz Shamir, in the HaGalil, or Upper Galilee.

Finally, the phrase itself come from one of the founders of Degania, the first kibbutz.

A little history, courtesy of Henry Near: Four young men from the Ukraine, who had participated in a Zionist group in the town of Romni, formed a commune and promised to share wages and accommodations once they boarded a ship for Palestine in 1907. The next year, now five, The “Romni Group” started work at a “training farm” at Kinneret, along the Sea of Galilee. Their relationship with the farm’s manager deteriorated, however, because of the manager’s over-optimistic profit estimates and, later, his use of Arab labour, which the Romni Group saw as “a violation of Zionist principles”. They held a strike and were asked to leave, although as a concession, they were offered a chance to cultivate a farm near the abandoned village of Um Juni.

They declined and, maintaining their communal arrangements, worked for different farmers near Hadera in 1909. Another group of six accepted the offer to work at Um Juni, which they did with some success, making a small profit, and then dispersed. The Romni Group were again offered the chance to move their communal arrangement to Um Juni, where the Jordan River flows out of the Sea of Galilee. This time, the Romni Group (now a dozen men and women) felt ready to grasp the opportunity and, in the autumn of 1910, returned to Galilee to found a community that, in August 1911, would be renamed Degania. (Hence, the problem of dating the centenary: Did Degania “begin” in 1909, 1910 or 1911?)

As Joseph Baratz, one of the founders, later recalled of their time in Hadera and their dreams of communal life:

Thanks to our communal life, a feeling of intimacy between the members grew up. We talked a great deal about the ‘commune’; for a certain time, this was the main idea … communal life not just for a chosen few, but as a permanent social system, at any rate for the bulk of the pioneers who were immigrating to Palestine.

…

Our chief aspiration was to be independent—to create for and by ourselves. We came to realize that it was a Sisyphean task to achieve this if we were working for somebody else, and we began to look back to Galilee.