Oct 24, 2012

For years, kibbutzes in Israel reliabley delivered the votes of their members to the left-leaning Labor Party (and its predecessors) in exchange for a guaranteed seat in the Knesset and (back in the days when Labor actually formed governments) a hand on the levers of the power. That decades-old wedding may be headed for divorce court.

News out of Israel suggests that the Kibbutz Movement is pissed off by a proposal, by new Labor head and former journalist Sheli Yachimovich, to combine the guaranteed seats for each the Kibbutz Movement and the Moshav Federation into a single seat that would represent the whole spectrum of Israel’s communal settlements. That doesn’t sit well with kibbutzniks, who always saw themselves as more ideologically committed as pioneers than the wishy-washy cooperative farmers on the moshavs—even if most kibbutzes have since “privatized” and operate far more like moshavs (or even gated country suburbs).

The article can’t resist a poke at the puzzling distinction between a kibbutz and a moshav—a huge difference to kibbutzniks but a bewildering hair-splitting to everyone outside their fences:

“An old joke best explains the distinction between a kibbutz and a moshav: if a kibbutznik had enough, he’ll probably move to a moshav (easier communal rules); but if a moshavnik had enough – he sure as heck is not moving to a kibbutz (even more stringent communal rules).”

Of course, the Labor Party bickering, amid polls that show right-wing Benyamin Netanyahu likely to form another coalition in the next election, only underscores the growing disfunction of the Israeli Left and the profound loss of influence (even among traditional allies) of the once powerful Kibbutz Movement.

Jun 27, 2012

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

May 7, 2012

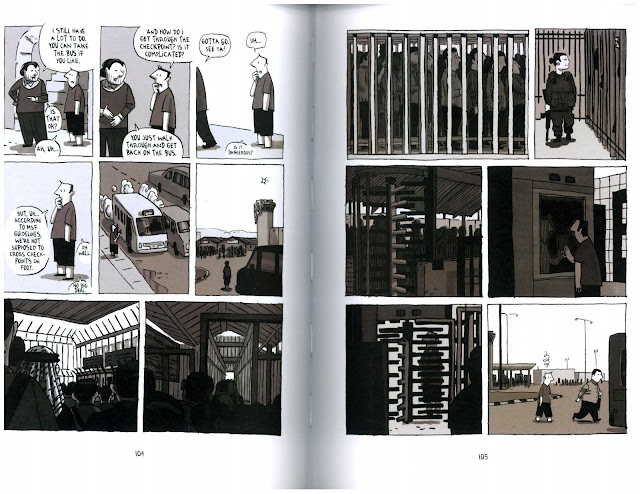

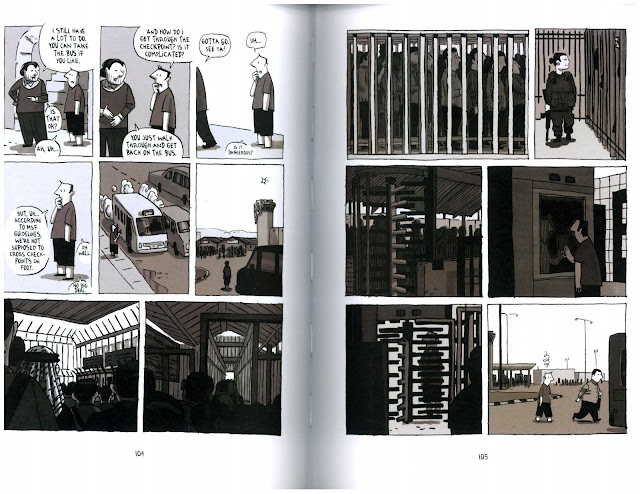

Guy Delisle’s new graphic travelogue, Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012), is framed with images of a plane arriving and then departing. In between, he recounts a narrative of the year he spent in East Jerusalem, Israel and the West Bank with his wife, who was assigned there for Medecin sans Frontieres (and who remains a distant presence, perpetually busy with her NGO work, throughout his book) and two young kids, Louis and Hanna, who occupy far more of his time.

A Quebecois animator and graphic novelist, Delisle strikes a wry, self-deprecating persona: a kind of bumbling house-hubby Everyman, naive, prone to faux pas while also quietly judging people based on how much they know and like comics. In Jerusalem, the world’s most complex city—an urban jigsaw puzzle drawn by Franz Kafka and die-cut by M.C. Escher—he finds an endless supply of paradoxes and ironies to befuddle him. What has become “normal” in Israel, East Jerusalem and the West Bank appears in all its tragedy and folly when described in minute journalistic detail. But the “journalism” practised by Delisle is as much eavesdropping and observing as researching and interviewing.

His sense of bewilderment begins when old Russian man with concentration camp tattoos lifts up and calms his crying daughter on the plane. It continues when he says “Shalom!” to the driver who picks them up at Ben Gurion Airport—and realizes he should have said “Salaam!”

The next day, an MSF officer tries to explain the political-geographical complexities of the city after Guy and his wife get settled into an apartment in East Jerusalem: They are in the capital of Israel according to the Israelis but in the future state of Palestine according to the international community, many of whom consider Tel Aviv the capital of Israel.

“I don’t really get it,” Guy reflects, “but I tell myself I’ve got a whole year to figure it out.”

By the end, though, it’s hard to know if he knows whether he has come closer or farther away from understanding the funhouse mirror chamber of identity and ownership in this densely packed (with people, with cars, with history, with religion) urban space.

He finds himself constantly caught off-guard by the the quirks, the rituals and the conflicts of all three major religions: the wail of the muezzin that wakes his daughter just after she goes to sleep; taking his family to lively West Jerusalem, only to discover it completely deserted on shabbat (“It reminds me of Sundays in Pyongyang,” he says); feeling guilty about munching an apple on Ramadan; the literally and figuratively Byzantine politics of the various Christian denominations jostling for influence (sometimes physically) over the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; or leading a comics seminar for veiled Muslim women, who are studying to be art teachers yet are prohibited by their religion from drawing people or animals.

When he mentions to a shawarma shop owner, in East Jerusalem, that his girlfriend “works for Doctors without Borders,” there is a long pause, as the owner slices off strips of meat, and then replies: “There’ll always be borders.”

Delisle tries to negotiate, as an outsider, the perplexing political nuances of life in East Jerusalem. He checks out a supermarket in a nearby Jewish settlement but resists buying his favourite cereal (Shredded Wheat, which he can’t even get in France) so as not to support the controversial West Bank settlements. But then, as he is leaving, he spots “three Muslim women loaded down with bags”. He visits protests at the checkpoints around the Separation Barrier and sketches the wall obsessively.

He gets moved most noticeably from his otherwise resolute neutrality—more a knowingly ignorant curiosity than high-minded journalistic objectivity—by three separate visits to Hebron: one led by an MSF staffer; another by a member of Breaking the Silence, the NGO that records testimony from Israeli soldiers; and a third by a right-wing religious settler who elides or even contradicts the stories Delisle has heard on the other tours. (The settler mentions only one of the city’s two infamous massacres.) The bitter separation between the tiny Jewish community and the larger group of Palestinian citizens of Hebron is poignantly symbolized by the netting strung over the souk, to catch garbage hurled onto Arab passers-by by angry religious settlers.

The month by month chronology of his family’s year in East Jerusalem gives the book an anecdotal quality, which gains resonance with repeated images or visits to different sites (like Hebron, or the wall, or Tel Aviv). No single incident acquires more prominence—not even Operation Cast Lead, the IDF assault on Gaza midway through his stay, which draws NGOs, like his wife’s, into a flurry of activity. Delisle’s later attempts to negotiate access to Gaza for himself get rebuffed when officials find out he is a comic artist. The imbroglio over the Danish cartoons of Mohammed has been in the news; Delisle also wonders if he hasn’t been mistaken for the more politically motivated comics journalist Joe Sacco.

One mini-chapter that most resonated with me is Delisle’s first visit to Ramallah, driven there by an acquaintance form the Alliance Francaise. “I’m quite surprised,” he notes. “I thought Ramallah would be a dead city, crippled by the conflict.” He meets a Palestinian animator who says it is easier for him to “get to London than travel five km to Jerusalem” for work. A foreign correspondent tells him: “Ramallah is like the Tel Aviv of the West Bank. People are freer and more open-minded here.”

Then Delisle’s acquaintance, who still has other business, suggests he take a bus back through the army checkpoint to East Jerusalem—technically, not allowed under MSF rules. What follows is the darkest page and a half of the book (literally, in the inky shadowing of the frames): 10 panels, without any text, in which Delisle depicts his claustrophobic point-of-view amid the crush of people queued to pass through the barred-in checkpoint for bus and foot traffic through the Qalandia checkpoint. (It immediately brought back my own memories of an hour and a half lined up at the same checkpoint.) He emerges into the light from the prison-like enclosure with a swirl of incomprehension over his own cartoon head.

That scene could be a metaphor for the book as a whole: a wise narrative filled with insightful observations that only prove how darkly puzzling and incomprehensible life in the holy—and wholly divided—city of Jerusalem really is.

Jerusalem is a must-read for anyone interested in this part of the world. (Download a preview here.)

I realize, of course, that there is not a single mention of a kibbutz in his book. But that fact is also telling: Delisle’s chronicle is about life in modern Israel, and especially the city of Jerusalem, and the kibbutz, as an institution that long symbolized the modern Israeli, is now increasingly divorced from and irrelevant to this reality.

May 1, 2012

It was great shock that I read, via Twitter, of the death (at age 60) of Abdessalam Najjar, one of the founders and leaders of Wahal-al-Salam/Neve Shalom—the village of Palestinians and Jews located near the Latrun Monastery. I’d interviewed him, in 2010, and found him a remarkable man: super-smart, funny, wise, an engaging storyteller, and a committed man of peace. I spoke to him for more than an hour, and knew throughout talk that I had to try to squeeze as many of his words as possible into my book (should I ever finish writing it).

Born in Nazareth, Abdessalam—perhaps more than anyone I met on my different trips—exemplified the utopian spirit of the original kibbutzniks. He had taken the path less travelled and chosen to live, in peace if not always harmony, with the people who he’d been taught were his enemy. He had helped to create in the “Oasis of Peace” a model that proved that Arabs and Jews could sit together and talk about their different situations, their competing narratives and grievances, could live together, could go to school together. That the walls of hate (and concrete, too) that had been erected too hastily could be pulled down, brick by brick.

I included a short transcript from our interview earlier on my blog. But Abdessalam had so much more to say—to me, to the world. It is a profound loss to his homeland and for the hope for peace over violence in Israel and Palestine.

Mar 21, 2012

[Yes, it’s finally time to emerge from my teaching shell and update my blog!]

A new book by Israeli author Amos Oz is cause to celebrate for any lover of world literature. But for a kibbutz-o-phile obsessed with the inside story of communal life, a fresh collection of Oz’s wry, ironically observed stories of life set on a rural commune can seem heaven-sent. And then you realize it’s still only in Hebrew. Which you don’t read.

Oh well, at least the weekend magazine of the newspaper Ha’aretz has published a long interview with the the 73-year-old ex-kibbutznik and elder-statesman of Israeli letters about his life, his politics, his literary influences and his new anthology of stories, Between Friends, set on apocryphal Kibbutz Yikhat. (Why it is so hard to find this level of literary discussion, let alone 5,000 words devoted to a writer, in a Canadian publication is another story…)

In the article, Oz talks about the utopian dreams of the kibbutz founders:

The first ideal of the kibbutz was sharp: to transform human nature instantaneously. Effectively, they [the founders] set out as a youthful camp, in the innocent belief that they would remain 18 and 20 forever. A camp of young people who were liberated from their parents, from all the prohibitions and inhibitions of the Jewish village and Jewish religion − a camp in which everything is permitted, suffused with perpetual ecstasy, and where life is always at a peak. You work, argue, love and dance until your strength runs out. It was childish, of course. In time, it became dulled. And then what came to the fore were the constants of human nature. The vulnerability, the selfishness, the ambition, the materialism and the greed. It was a forlorn dream, imagining that it would be possible to triumph over all those forces, be reborn and create a new human being without the shortcomings of the old one

He discusses why he left Kibbutz Hulda (because of his son’s health), and how his new collection allowed him to reflect on what he left behind, good and bad:

There were a few things I didn’t like about kibbutz life. But I feel the absence of those things that I did like. And in this book I wanted to go back and look at them. Especially at the loneliness in a society where there is (supposedly) no place for loneliness. In a few of the stories a situation is portrayed of “almost touching”: People very nearly touch, but something blocks it. Like in the painting by Michelangelo where finger almost touches finger.

I am very curious about loneliness and grace, or a moment of grace amid loneliness, because that is a description of the human condition. The stories are set on a kibbutz, but they tell about universal situations, about the most basic forces in human existence. About loneliness. About love. About loss. About death. About desire. About forgoing and about longing. In fact, about the simple and profound matters which no person is unfamiliar with.

He explains how curiosity can make us more “moral”—that, in effect, literature’s ethical function isn’t necessarily to teach us lessons but to let us see the world through another’s eyes:

I think a person who is curious is slightly more moral than one who is not curious, because sometimes he enters into the skin of another. I think a curious person is even a better lover than one who is not curious. Even my political approach to the Palestinian question, for example, sprang from curiosity. I am not a Middle East expert or a historian or a strategist. I simply asked myself, at a very young age, what it would be like if I were one of them.

He admits he still has no regrets about living (and leaving) on a kibbutz. Writers will be especially interested to hear Oz discuss how communal life offered the ideal milieu to develop his literary ear and eye:

I do not regret it for a second. I regret a few of the experiences my children underwent on kibbutz. There were some hard bits, but I left Hulda without anger. For me, the kibbutz was an ultimate university of human nature. I spent 30 years with 300 people in intimate proximity. I saw everything − them and their lives − and knew their secrets. If I’d spent 30 years in Tel Aviv, or New York, I would not have had the slightest chance of becoming so intimately acquainted with 300 souls. The price was that they knew more about me than I would have wanted them to know. But that’s a fair price. In terms of my writing, I learned much of what I know about human nature on kibbutz.

And I love his metaphor for how he has come, if not exactly to praise the kibbutz, then definitely not (like so many critics in recent years) to slay this once-legendary institution:

Unlike others, I am no longer slaughtering sacred cows. There was a time when I did. Not today. Besides which, in every cowshed there is one sick old cow left, surrounded by a herd of exultant, gung-ho slaughterers. I am almost always on the side of the cow. It’s not that I don’t know what a foul smell that cow gives off. And it’s not that I worship it. But between the cow and the slaughterers who gather around − I prefer the cow. I am talking about Zionism, the kibbutz and the labor movement.

Dec 21, 2011

If it walks like a kibbutz and talks like a kibbutz—or rather, looks like a kibbutz and works like a kibbutz—then surely it must be one, no? That was the question I puzzled over, on my recent trip to Israel, when I stayed for four days and nights on the fascinating community of Nes Ammim.

First a correction: In a blog post from the road, I hastily described Nes Ammim as a “German-run kibbutz”. People there, who had googled my blog, quickly corrected me. Yes, there are Germans among the leaders and volunteers. But Nes Ammim was founded, in the early 1960s, by Dutch and Swiss citizens, led by Dr. Johan Pilon from Holland and Dr. Hans Bernath from Switzerland, both physicians working in the Galilee. Americans volunteers arrived later, as well as a steady contingent of Germans—but only after German nationals were finally permitted to visit Israel. (A basic history can be found here.) But German-run? Hardly!

|

| A rose by any other name: erecting the “glass houses” |

My confusion, perhaps, is understandable. Nes Ammim confuses the basic definition of a kibbutz. When most people picture a kibbutz, they imagine a rural settlement of secular Jews, founded by blue-shirted pioneers inspired by the ideals of utopian socialism. Marxist farmers with bronzed arms and short-shorts. (Yes, there are a handful of religious kibbutzes, but they never played as large a role—except for Kfar Etzion—in the mystique of the kibbutz movement.) People never imagine a village of blonde Christians growing roses.

Nes Ammim isn’t even on the radar among kibbutzniks within Israel. When I told Israeli friends and acquaintances that I was visiting a kibbutz of European Christians, they gave me incredulous looks, as though I’d said I was staying with the Tooth Fairy: they had never heard of Nes Ammim. In fact, after four years of intense research into utopian communities throughout the region, I only stumbled across the website for this community by accident, a couple of months before visiting.

On my first afternoon in Israel, in late November, as I entered the grounds of Nes Ammim, it certainly felt like I had arrived at a kibbutz. There were the surrounding fields, the gate (open) and guardhouse (empty), a swimming pool and a carpentry shop, a dusty ring road and winding pedestrian paths, the rudimentary tin-roofed volunteer cabins, with everything focused on the the dining hall and office complex at the centre of the property. The kitchen has a bit of a split personality on Nes Ammim. Most of the kibbutz’s revenue now comes from its guest house, popular with Israelis escaping the summer heat and Europeans escaping their own winter, so the kitchen prepares food for tourists in the restaurant as well as residents and volunteers in a more barebones, buffet-style communal dining hall.

The original kibbutz movement had two goals: establish the borders of a future state in Palestine for the Jewish people (ie, Zionism) and create a new model for living in equality (ie, utopian socialism).

So what was the founding vision of Nes Ammim? Obviously not the first: Israel existed by the time the idea for Nes Ammim arose. And the second? Perhaps only tangentially—certainly the spirit of radical sharing was in the air at the time. But the founders of this unique community had a more specific goal in mind: to create a community within the young state of Israel that would help Europeans and Christians, and especially European Christians, emerge from the dark shadow of the Holocaust, from millennia of pogroms and anti-Semitism, and heal the deep chasm of suspicion with the Jewish people. It would be a new community, modeled on the successful Jewish invention of the kibbutz, where dialogue groups and encounter sessions between leaders of the two religions could take place. The name of the kibbutz—Nes Ammim—means “a banner for the nations” and comes from the Book of Isaiah. It refers to God’s promise of everlasting peace in paradise for all the people on earth, which will be announced by such a sign.

The idea for Nes Ammim earned the support from kibbutz leaders (it would become an associate member of the movement) and Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. However, influential rabbis worried that Nes Ammim would be a front for evangelizing Christians trying to convert Israeli Jews. They opposed the plan—and the community—for many years. Once rumours circulated, thousands of people in nearby Nahariya marched in protest, too. The founders only got government permission to settle the property, purchased from a Druze sheikh, after they signed an agreement that promised never to proselytize. Every new volunteer must sign a similar “no-preaching” contract.

|

| Swiss Family Kibbutznik: the famous bus at Nes Ammim |

In 1963, a Swiss family drove a rickety old school bus with faulty brakes—a “gift” from Israeli friends—off the heights of Nazareth and across the untilled fields of the property. They parked on a hill: the bus would become the first building of Nes Ammim. It remains today as a museum and a reminder of its ad-hoc origins. Slowly, residents and volunteers who moved to and lived on Nes Ammim earned the trust of their Jewish neighbours, in part by never abandoning the settlement during the six wars that threatened the nation. Eventually, Germans—who weren’t even permitted to visit Israel during its early years—were permitted to stay as volunteers in the 1970s.

Nes Ammim developed a communal economy around avocado orchards, olive groves and its famous “glass houses”: greenhouses that deployed the horticultural expertise of Dutch residents to grow and sell roses. Bouquets of Nes Ammim roses became a sought-after decorative element at receptions for visiting foreign dignitaries. While the settlement was always intended to be permanent, residence there wasn’t. Leaders stayed on Nes Ammim for perhaps five or six years at most and then returned home. Volunteers usually lived there for a year or less. The kibbutz followed this pattern for years, slowly growing, adding buildings and residences, while new people cycled through and gave it energy and life.

Like the rest of the kibbutz movement, though, the turn of the millennium saw Nes Ammim suffer an identity crisis. The community could no longer compete with cheap flowers imported from Africa and had to shut down the glass houses—for decades, the signature feature of its economy. The violence of the Second Intifada and the Second Lebanon War cut into bookings at the guest house.The population of European families moving there had declined and many of the houses were being rented out to Israeli tenants.

And there were existential questions, too: What was the purpose and value of this place, 40 years after its founding? The European attitude toward the state of Israel—once wracked with guilt, now more aligned with the plight of the Palestinian people—was also shifting. How should Nes Ammim react to these changes? Could it evolve with the times?

I had walked unknowingly into the midst of this debate. For the last few years, Nes Ammim has focused not only on dialogue work between Christians and Jews, but also between Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews. The site of the kibbutz, leaders realized, could be used as neutral ground (or as neutral as any ground gets in Israel) for different groups within the country to meet and talk and build trust.

Nes Ammim had just broken ground on an even more ambitious project. Like almost every other kibbutz in the country, they are building a rural subdivision to be marketed to outsiders. Unlike almost every other kibbutz, Nes Ammim plans to use a new law that allows community settlements, in the country’s north and south, to interview and select residents—to screen newcomers, in other words—as a way to populate a mixed neighbourhood of Arabs and Jews, much like Neve Shalom/Wahat-al-Salaam. (This law has proven controversial, and come under legal challenge, because it has been used to exclude Arab residents interested in moving into Jewish settlements. Of course, membership by vote has been the kibbutz model from the very beginning.)

Not everyone I spoke with at, or associated with, Nes Ammim was keen on these changes. Some doubted that the community would attract enough Jewish residents to balance the population of this new neighbourhood. Others worried that Nes Ammim would lose the European character that had made the place unique, and with it, the focus on healing the division between Christianity and Judaism, between modern Europe and modern Israel, which has only grown in recent years.

The young Dutch and German volunteers I met on Nes Ammim, however, seemed excited by the prospect of change. Their experiences on the kibbutz had been enriched, they told me, by the opportunities to see and hear about the complex nature of Israel from multiple perspectives: to learn Hebrew from native speakers, to tour the Holocaust Museum at the nearby Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz, to teach English to kids at the next-door Arab village, to meet school groups from both sides of the conflict, to visit the West Bank, to realize how many shades of grey exist behind the black-and-white stories of the region they were fed by the media back home. (I was envious of the rich experience these volunteers were getting on Nes Ammim, a far more intimate and honest look at life in Israel—especially the mixed Arab-Jewish region of Western Galilee—than 99.9% of foreign visitors will ever encounter.)

Nes Ammim was a place, sleepy as it might seem, that will always attract a whiff of controversy. How can you bring different religions together and not expect some friction? Perhaps that tension between its harmonious aspirations and its contentious reality is best symbolized in the sculpture that rests in the foyer of the kibbutz’s “church”. The building itself has been largely stripped of evidence of any faith or denomination. No cross, no icons, nothing but chairs facing a bare altar. The entrance, with a koi pond and rock garden in its centre, has the aura of a Zen Buddhist sanctuary more than anything else.

Then your eye is drawn to the sculpture in the pond, like a nativity scene floating on a disc. Three sets of ten figurines face a central pillar with three doors. The terracotta-coloured figures are arranged in a V-shaped 1-2-3-4 pattern, like bowling pins, aimed toward the three-doored hub. A closer inspection reveals the particulars of each faith in the figurines’ genuflections: Muslims prostrate on the ground, Christians kneeling, Jews—a minyan of them—standing, heads bent, holy books in hand.

|

| A pool for prayer: the many-layered sculpture at Nes Ammim |

The symmetry of the design is meant, of course, to suggest a harmony between these faiths, a place of coming together. It isn’t always read that way: Why does one door look more open than the others? What is meant by the hierarchy of the figures’ stances: standing, kneeling, prone? And as a few visitors have asked: Where are the Druze? The Ba’hai? Aren’t there more than just three faiths in the area?

I was told that the kibbutz members had to erect the low wire barrier that surrounds this installation because curious observers and anonymous sculpture critics, either by accident or design, kept inspecting the set-up and knocking over the figurines. You can see where the heads of decapitated worshippers have been glued back on. So now, in Nes Ammim, a place of faith and healing, a Christian utopia for Jews and Muslims, a fence must guard even this representation of their equality before the Almighty, this microcosm of the community’s higher ideals.

The sculpture is, quite literally, a “floating signifier”—a symbol even more symbolic than it was originally intended.

Dec 20, 2011

Few communities illustrate the contradictions of the contemporary kibbutz more than Sasa. This community (often called the “first all-American kibbutz”) was founded by North American immigrants and members of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair movement in the aftermath of the 1948 war on the high country near the border with southern Lebanon. It remains among the dwindling number of kibbutz shitufi—fully communal in its economy. It has also been, over the last decade, the most financially successful of the 270 kibbutzim scattered across Israel.

Evidence, it would seem, that you can maintain a kibbutz’s traditional philosophy of peace and equality and still thrive as a community. That capitalism doesn’t trump all.

Well, not so fast.

The ideals of Sasa, while strong, are still compromised in revealing ways. The kibbutz was founded on the ruins of an Arab village, destroyed and depopulated during the War of Independence. An interview with one of the founders, in Toby Perl’s excellent documentary about the kibbutz movement, reveals an ambivalence about settling the site after the new arrivals realized its recent and troubling history—the ghosts that dwelled there, the original occupants now refugees across the border with Lebanon. (They stayed nonetheless.)

A similar asterisk must be added to Sasa’s economic success, which has allowed it to maintain its communal ideals. The members didn’t get rich growing grapefruits or (as at other kibbutzim) making plastics or irrigation devices or bifocal lenses. They made millions and employed thousands over the last 10 years by selling armored plating to the American military via the Plasan factory. In other words, the kibbutz was one of the main beneficiaries (along with shady military suppliers like Halliburton) of the the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

|

| The wheel thing: A Plasan-made “Sandcat” combat vehicle |

The recent American withdrawal from the former and scaling down of operations in the latter have affected the economy of Sasa. News recently circulated about lay-offs at the kibbutz factory, and the Kibbutz Industries Association cited a drop of 13% from the nation’s kibbutz-based industries, largely as a result of the decline in profits at Sasa.

Peace dividend?

Not at Sasa. In this unusual utopia in the mountains, communal life has been preserved, and difficult decisions deferred, in part, thanks to the exorbitant American expenditures on foreign wars. Of course, one could always argue that Sasa didn’t manufacture weapons per se, and instead made its money keeping soldiers safe against improvised explosive devices and land mines. But that seems like splitting hairs. This kibbutz remains intermeshed, more than any other perhaps, in the global military industrial complex. What will it do now that the U.S. Armed Forces’ money machine has been turned off? Can the community’s values survive in times of peace as well as war?

Nov 26, 2011

After a more or less smooth trip (as smooth as getting up at 3 am for a taxi, two planes, a train and a rental car can be), I made it to Israel and have slept off most of my jet lag. I paused briefly, to rest and get my bearings at Nes Ammim—a “kibbutz” of German Christians in between Nahariya and Akko. I return there tomorrow for three more days to learn about their history, their evolution, and the interfaith dialogue workshops they run, as part of their dream of healing the rifts between Germans and Israelis, Christians and Jews.

On Friday afternoon, I drove north to the Hula Valley and my old kibbutz at Shamir. I’m staying with friends and visiting old acquaintances and, later this morning, interview Uzi Tzur, the first-born ben kibbutz (i.e., child of the kibbutz), who has played a huge role in both the defense of Shamir (he shot the terrorists who tried to infiltrate the kibbutz in 1974) and the success of Shamir Optical as a multinational enterprise.

I made it in time foe one more shabbat dinner on Shamir, always one of my favourite nights (the weekend, at last!) when I was a volunteer. The dining hall is privatized (open for lunch and Tuesday and Friday dinners now), and was maybe two-thirds full—not quite the clamouring packed hall from years past, but still alive with conversations between old friends and family members. You pay for your meal now, at the cash register till, and there is no longer free (albeit cheap and watery) white wine to be poured into jugs by the litre from industrial beverage dispensers.

I’d seen evidence of religious leanings on other kibbutzim, but Shamir seems still to be resolutely secular: no prayers, no candles, no shabbat songs, none of the Jewish rituals I’d witnessed at erev shabbat on Kibbutz Lotan in the Arava or the Ravenna Kibbutz in Seattle. If anything was sacred here, it was the family—Shamir seems in the midst of a baby boom—and Friday night, the communal dinner was honouring the extended family, related by blood or proximity, so central to kibbutz life.

Yesterday, after a restful sleep-in, my friends Kari and Danny took me for a shabbat day trip. We tried to go to the Agamon-Hula Park, but the parking lot was crammed with bird-watchers and other tourists for the annual Hula Bird Festival—the valley’s blue sky is alive with migrating cranes and hawks and other Rift Valley migrants—so we headed up north, nearly to the Lebanese border, and walked the forest trails (much quieter) of Tel Dan instead. We had lunch beside one of the streams that feeds the Jordan River.

The Hula remains as beautiful as I remember, this crook of farm fields and marsh land, peppered with kibbutzes and moshavs, in between the Golan Heights and the Napthali Mountains. It has been a pleasant reminder of my time here 22 years ago, during the same autumn season when I first arrived as a volunteer, the days still sunny and yet the nights cooling quickly, the rainy season and the cold winds off the snowy top of Mt. Hermon on the horizon. Harvest over, a new year marking off its days.

Nobody seems optimistic about the immediate future of Israel, with the looming showdown with Iran and the uncertain changes in neighbouring countries, with a right-wing government firmly entrenched in power and completely at odds with the traditional values of the kibbutz. But it’s hard not to find a certain peace, here in the hills of northern Galilee, amid the tree-shaded lanes and bird-song and cries of children in the playground, here on Kibbutz Shamir.

Nov 23, 2011

I’m excited (and nervous) to be in transit again, for a two-week research trip in Israel. I’m hoping that my interviews there will cap off all the material I need to complete my book. (Actually, what I need is the discipline—and perhaps a manacle around my ankle—to simply buckle down and finish a first draft.)

The next 14 days promise to be a flurry of travel and meetings and interviews and observations. Some highlights from my itinerary:

- Nes Ammim: A German-run interfaith “kibbutz” that coordinates dialogue workshops and peace-building initiatives. I’m hoping to drop in on a session with Arab and Jewish theatre students from Haifa.

- Kishorit: a former kibbutz that has been transformed into a rehabilitation centre and home for adults with physical and mental disabilities, where they can find meaningful work (including producing a TV show) and community.

- Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company: I had brief visit to the studios and rehearsal spaces on Kibbutz Ga’aton 2.5 years ago, but on this visit I will spend time talking to artistic director Rami Be’er and then seeing this internationally renowned troupe perform in Tel Aviv.

- Ran Tal, the director of the “collage” documentary” Children of the Sun, which weds archival footage of kibbutz children, from the 1930s onwards, with interviews with early kibbutzniks (including Tal’s mother) about the positives and negatives of growing up (and raising their own children) in these isolated and idealistic communal outposts.

- System Ali, a hip-hop collective, with members who are Arab and Jewish, native-born Israelis and Russian immigrants, that sprung from the Sadaka Reut commune that I visited in the summer of 2010.

- Eliaz Cohen, a poet from Kibbutz Kfar Etzion, one of the most historic settlements, who writes verse informed by his deep spiritual roots and his communal home.

- And more…

First, though, I’ve got a 10.5-hour flight to Tel Aviv (with an exit-row seat!), negotiate the 20 Questions of Israeli Customs, grab an hour-and-a-half train ride to Nahariya, rent a car there, and make the short drive (thankfully) to Nes Ammim. The next morning I hit the ground running with interviews and then a drive up north to Kibbutz Shamir. No time for jet lag.

Nov 16, 2011

I’ve been a lazy blogger of late, but not because I’ve been ignoring my kibbutz project. Anything but. The last month or so has been a hectic swirl of activity. I’ve been pounding my keyboard to finish a draft of the book by the end of the year. (Increasingly unlikely, although I’m pushing 140,000 words now.) I’ve been preparing for another research trip to Israel, which I’m very excited about. (I leave in less than a week; details to come.) And I’ve been writing and rewriting and practising a talk, linked to my research, for the upcoming TEDxVictoria conference this Saturday, November 19.

The 15-minute talk is called “Kibbutzing Your ‘Hood”. Without giving too much away, I will try to distill the wisdom of kibbutz design—the “architecture of hope” upon which these communities were built—and apply it to our own cities and neighbourhoods in North America. Some of the ideas I hope to bring together and share: the link between kibitzing and kibbutzing; the secret family history that joins Israel’s famous socialist communes and the suburbs of North America; the unexpected social effects of unfenced open spaces; the importance of “third places”; how to calculate your neighbourhood’s “K.Q.”; and how the tools of micro-media can help communities turn positive gossip into enduring myths that will sustain them into the future.

Or something like that.

That’s the teaser. Come on down (I think tickets are still available), if you live in Victoria, to what should be a fascinating roster of speakers and performers and discussions. I’m thrilled to be part of this event—and to sneak a little kibbutz philosophy into the audience’s imagination.

As part of the TEDx mandate, online videos of each talk will be posted. I’ll add a link to my session as soon as it’s up.

Oct 5, 2011

Okay, if someone let me design my perfect bookstore, what would it look like?

First, I’d want to pedal to it, so I’d put a decent stand for locking bikes, covered from rain of course, right by the front door. Maybe keep a stand pump handy in case anyone gets a flat. I love reading outside, so let’s include a patio section for a coffee and a book en plein air.

Inside the entrance, I’d expect to find a good selection of magazines—local, national and international—literary journals, maybe a few zines. Some tables with new releases: hardback and soft, fiction and nonfiction. A big corner devoted to kids’ books.

I’ve always been a used book-buyer, so a good chunk of the store ought to be devoted to recycling other people’s past purchases, with a big desk at the back to make it easier for sellers to unload their offerings. In our era of infinite opinions and online retailers, a bookstore only matters if it’s got a personal touch, so I’ll let employees hand-write recommendations for their favourite books and leave their comments tucked as teasers between the shelves. Teachers, of course, are the most noble profession, so we’ll give them a 20% discount.

All that designing has made me hungry, so I’ll want a place to eat. Make it a cafe, with hot lunches and a dinner menu, great coffee, fresh muffins and other treats. Offer traditional cafe seating, but add a kids play area and then another section, next to the windows and also looking out across the bookstore, where people are encouraged to hang out, chat, read, work on their laptops. (Free wireless, of course.) Encourage them to stay. Make them feel so at home that they wheel in their double-stroller and dog.

Anything else? Well, throw a whole series of readings and talks and musical events. And there’s the downstairs… let’s turn it into a bar with 15 beers on tap, because, hey, I already belong to a “Beer & Books” group, so the guys might as well have a special place to hang out.

Oh wait, what’s that? Somebody already built my literary utopia?

So they did. And in Seattle, no less.

I flew across the Strait last Friday to have shabbat dinner at the Ravenna Kibbutz (more on that later). Because of my arrival time, I had about six hours to kill before dinner began. I tried to scope out the closest library, but it was closed—on a Friday! (Budget cutbacks.) And that’s when I discovered the Ravenna Third Place bookstore (and cafe and pub), just blocks from the kibbutz, and a perfect complement to my research into community values and communal spaces.

This unique twist on the bookstore/cafe combo has been explicitly designed around the idea, by sociologist Ray Oldenburg, of the “third place”—the communal space that is neither work nor home, that is free or inexpensive, accessible and inclusive. A place to kibitz. In his book The Great Good Place, Oldenburg describes these civic sites and establishments as centres of “informal public life”, where networks of affiliation can develop and creativity can spark.

Inspired by this vision, The Ravenna Third Place’s website and bookmarks welcome newcomers to a “deliberate and intentional creation of a community of booklovers. A fun and comfortable place to browse, linger, lounge, relax, read, eat, laugh, play, talk, listen and just watch the world go by.”

I did most of the above. I nursed a latte for close to four hours, wrote in my journal, chatted to a couple of the servers (I’d wanted to interview the owner, but he wasn’t in), daydreamed, people-watched and eavesdropped on everyone around me. One young guy was doing animation on his laptop. Another middle-aged man was studying Chinese on his computer. Behind me, a young university student (from Arkansas via Alaska) was meeting for the first time a pastor who organized a fellowship group she was curious about. (Yes, we were in Richard Florida’s “creative class” Seattle, but also George W. Bush’s evangelical America.)

Finally, I browsed the bookshelves and went home (after my “educator’s discount”) with a used copy of Amos Oz’s Elsewhere, Perhaps and the new paperback edition of Sarah Bakewell’s inventive How to Live.

I returned to Victoria wishing I had my own Third Place so close by. (There are a few cafe/bookstores around town, but none as ambitious as this.) If you build it, I will come. And stay for hours apparently.

Sep 27, 2011

I had a “kibbutz moment” this past Saturday.

It was the last weekend of September, and fall was definitely looming. One of the neighbours on our cul de sac had the brilliant idea to suggest a street party for that evening. We’d had one party, usually an impromptu annual event, earlier in the season. However, new owners had moved into houses sold over the summer and pair of younger longtime residents were moving out of their parents’ homes at the end of the month. It would be a good chance to say hello and goodbye at the the same time.

It turned out to be a perfect night: likely the last warm, breezeless evening of the year. We pulled out a barbecue and tables and chairs and spread out a huge potluck (heavy on desserts). Our kids chased each other (and huge bubbles) around the cul de sac and drew chalk drawings across the pavement. Names were put to new faces. Recently departed neighbours, already much-missed, were invited for a noisy reunion. In the distance, a soundtrack from the Rifflandia Festival drifted from Royal Athletic Park. It reminded me why we had moved here in the first place and then undergone the trauma of renovating our house, when it seemed too small for two kids, rather than moving elsewhere.

The street party evoked memories of the barbecues and bonfires we had on the kibbutz, in the scrubby commons in between the volunteers’ quarters, drinking beer and swapping stories. It also echoed many of the themes and ideas and values I’d been reading about in a wonderful new book by Ross Chapin, an architect from Whidbey Island, Washington, called Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small-Scale Community in a Large-Scale World. In this compellingly written and beautifully designed volume—an eye-pleasing coffee-table book with the intellectual urgency of a political manifesto—he lays out the historical precedents of and design principles for human-scale developments, built to promote communal interaction rather than enforce privacy and facilitate car travel, what he calls the “pocket neighourhood”.

|

| A “pocket” get-together in Umatilla Hill, Port Townsend, Washington, designed by Ross Chapin |

Chapin and his firm have purpose-built a number of these “pocket neighbourhoods” in the Pacific Northwest. At the most basic level, the ideal pocket neighbourhood consists of a number of key features:

- first and foremost, a central grassy common area or open courtyard, into which all of the houses (and their covered porches) face, connected by shared pathways and gardens;

- a central commons building, including a kitchen and dining area, in which indoor group activities (during rainy weather, say) can take place and shared equipment can be stored;

- smaller homes—one or 1.5-storey cottages, rather than mammoth monster houses that dominate the sight-lines;

- low or no fences, rather than high barriers between neighbours;

- and—very important—cars and other vehicles shunted to the margins, kept to adjacent lots or back alleys, so that houses aren’t dominated by garages and common spaces intimidated and interrupted by traffic.

In other words: Build a ‘hood that encourages what Chapin calls a “web of walkability” and the serendipitous encounters that occur once you free your ass from your car seat.

The book provides a wide array of sketches and photos from the developments that Chapin has pioneered, complemented by historical antecedents (Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard; Hofje almshouses in Holland; Forest Hills and Sunnyside Gardens, both in Queens, and other neighbourrhoods inspired by Ebenezer Howard’s “garden city” vision; Village Homes in Davis, California; SoCal’s bungalow courts; floathome communities); contemporary examples of and ideas for creating pocket-like features in existing neighbourhoods (traffic-slowing lanes and woonerfs; backyard cottages; “defencing” backyards; “sagine communities” for retirees; cohousing projects; Earthsong in New Zealand and Christie Walk—an “urban eco-community” in Australia; Swan’s Market in Oakland; community gardens, cul de sac commons—and potlucks!—alley greening; intersection painting in Portland… on and on!); and short profiles of visionary architects, planners and neighbourhood activists (Mark Lakeman of Portland; Karl Linn, a kibbutz founder who went on to teach landscape architecture at UPenn; Jim Leach—no relation—the largest cohousing developer in the U.S.; Paul Downton of Ecopolis Architects; Jan Gudmand-Høyer, who studied the kibbutz movement and then pioneered Danish cohousing models; investment advisor Catherine Fitts, who invented the “popsicle index” of community health; Judy Corbett of the Local Government Commission; Hans Moderman, the counter-intuitive traffic engineer and woonerf pioneer who realized that to calm traffic you had to confuse drivers).

So many of the key concepts outlined in Chapin’s “pocket neighbourhood” vision have been part of the philosophy of kibbutz design for 70+ years. In fact, using some of his tips to turn any street into a “pocket neighbourhood” would be a good example of what I’ve been calling “kibbutzing your ‘hood”: that is, integrating the connections essential to community life right into the built space. Best of all, you don’t have to be a radical socialist to live in a pocket neighbourhood; they are designed, in Chapin’s perspective, to balance our desire for personal privacy with our innate human sociability. These more closely interconnected streets and neighbourhoods also create what he calls (on his website but not in the book) a network of “shirt-tail aunts and uncles”—neighbours who watch out for each other, who have a stake in the safety and healthy development of the children (and adults) around them. (We’re lucky enough to know several.) It takes a village. Or at least a pocket neighbourhood.

I’m hoping to talk to the author in person at some point to learn more about the theory and practice of pocket neighbourhoods, and perhaps compare notes with my own research into the principles of kibbutz design. In the meantime, I’ve been inspired by his optimism that we can create a more rich and sociable community on our own—and also a little envious of those developments he has already created, in which neighbours have been given a central traffic-free commons in which to come together, every day, and build a community one conversation at a time.

Ross Chapin. Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small-Scale Community in a Large-Scale World. Taunton Press, 2011

Sep 23, 2011

Amos Oz has claimed that there is no such thing as a “kibbutz literature”. Yes, there are books written by kibbutzniks and books written about kibbutzniks. However, even after 100 years of kibbutz life (and nearly as long writing about it), no motif or technique unifies all these spilled words other than a setting. “The kibbutz,” Oz has argued, “has not inspired any ‘mutation’ in Hebrew literature.”I won’t disagree with Oz: He is Israel’s most-famous author, a (former member of Kibbutz Hulda for 30+ years, and a widely quoted authority on matters literary, communal and political. (Would someone give the man a Nobel Prize already?)

That said, if there were a kibbutz literature, Oz’s first novel (and second book, after his debut collection of stories, Where the Jackals Howl) Elsewhere, Perhaps deserves a place of honour as the classic text in the transitional period from the “heroic age” of the kibbutz to its modern depiction as a complex, troubled microcosm of the greater world around it. Oz’s dedication (to the memory of his mother) tries to throw off the reader by demurring: “Do not imagine that Metsudat Ram”—the book’s fictional kibbutz, near the Syrian border and the Sea of Galilee—”is a reflection in miniature. It merely tries to reflect a faraway kingdom by a sea, perhaps elsewhere.” Oz has said, several times, that he had been inspired as a writer by Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, to realize that literature could find universal resonance even within the confines of a small, otherwise nondescript community. That stories didn’t need to happen in New York or Paris or Moscow to matter. Kibbutz Metsudat Ram becomes Oz’s Wineeburg.

As it tells the story of this settlement, from the multiple perspectives of different kibbutzniks, the novel draws tension from a trio of love triangles: one that has happened and left a bitter fallout; another—in part a consequence of the first betrayal—has become the recent focus of kibbutz gossip; and the third melodrama develops and concludes over the course of the novel. Socialism and Zionism may be the ostensible philosophies of the kibbutz, but the urgings of the heart (and lower regions of the body) drive many of its members’ actions. The howls of the jackals and the unseen, unnamed “enemy” in the jagged hills beyond the wire fence of the well-ordered kibbutz suggest external forces of chaos that threaten the community, and yet human impulses within its gates—the casual adultery, the malicious whispering, the vandalism of bored youths—prove more corrosive.

The timing of the novel’s publication is significant. It was published, in Hebrew, in 1966, the year before victory in the Six Day War (in which Oz fought in the Sinai campaign) transformed the young nation of Israel in ways that it is still reckoning with. Before 1948, the kibbutz was the pre-eminent form of settlement in pre-state Israel, the pioneers who helped lay down the borders for the future nation; after 1967, their reputation as nation builders diminished and was overshadowed, controversially, as religious and right-wing settlers began to move into the occupied West Bank and Gaza. (A few secular kibbutzim were built beyond the “Green Line”, but the movement otherwise remained focused on growing its existing communities and building new ones within the 1948 borders.)

Beyond this historical context, though, Elsewhere, Perhaps suggests a distinct technique of “kibbutz literature” through its narrative voice. While Oz drifts into the consciousnesses of various characters, the book begins and ends and speaks throughout in the collective “we” of the kibbutz as a whole. It is a subtly ironic “we”, a slightly naive “we”, though, a voice that, while trying to justify the ways of the kibbutz to readers and other outsiders, doesn’t always recognize the flaws in the community or its residents that are there to be read between the lines. The “we” sounds a bit like first-person plural narrator of Jeffrey Euginedes’ The Virgin Suicides (told in the collective voice of the boys who observe the mysterious lives and deaths of the Lisbon sisters on their suburban street) or the “downstage narrator” of a Tom Wolfe essay or nonfiction novel, which takes on the verbal tics and biases of a group rather than an individual character.

“Our village is built in a spirit of optimism,” this narrator tells us, and yet optimism seems hard to come by in the settlement of Metsudat Ram. Perhaps, notes the narrator, readers have an overly nostalgic, romantic image of village life: “The object of the kibbutz is not to satisfy the sentimental expectation of town dwellers. Our village is not lacking in charm and beauty, but its beauty is vigorous and virile and its charm conveys a message. Yes, it does.” One of the most telling passages (and most relevant to my own interest in the history of the kibbutz) talks about the vital power of gossip on the kibbutz. The narrating “we”, in many ways, is gossip personified—is a reminder that perhaps all storytelling, all literature, begins as gossip, as tales traded between neighbours:

“Gossip plays an important and respected role here and contributes in its way to reforming our society. … Gossip is simply the other name for judging. By means of gossip we overcome our natural instincts and gradually become better men. Gossip plays a powerful part in our lives, because our lives are exposed like a sun-drenched courtyard. … Gossip is normally thought of as an undesirable activity but with us even gossip is made to play a part in the reform of the world.”

As a money-less, anti-authoritarian, utopian settlement, the kibbutz is based instead on a “reputation economy”. As the narrator reminds us toward the end of the book: “The community can neither exercise brute force nor hold out promises of material gain. Our system compels us to rely entirely on moral sanctions.” Those “moral sanctions” consist of the raised eyebrow, the cold shoulder, the awkward question, the whispers that circulate around the dining hall—a complex semaphore that signals a community member’s rising or falling social standing. Gossip holds the kibbutz together, as the narrator makes clear. But the novel also asks: At what cost?

Amos Oz, Elsewhere, Perhaps. Translated from the Hebrew [Makom aher] by Nicholas de Lange, in collaboration with the author. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1966, English Translation 1973.

Sep 12, 2011

Over the past century, more than 400,000 volunteers from around the world have worked on a kibbutz for at least a couple months. Some found love (or other good reasons) to stay for good. Most returned home, changed in ways small or large. Inevitably, given their numbers, a few of these gangly teenaged volunteers and globe-trotting twenty-somethings went on to greater renown as authors, actors, academics, as politicians and pundits.

Novelist Arthur Koestler (best known for his anti-Stalinist parable Darkness at Noon) was one of the first volunteers to put his memories to paper. He had abandoned his university studies in Germany in 1926, acquired a visa to Palestine and arrived in Haifa with plans to work on a kibbutz, to be a true settler—even though he was an aspiring writer from the city with little taste for physical labour.

He was shocked by the primitive conditions on Kibbutz Hephizibah, which he described as a “rather dismal and slumlike oasis in the wilderness”. He had expected hardy log cabins, like those of the American pioneers. Instead he got ushered into “ramshackle dwellings” that reminded him of the poorest slums of Europe. Kibbutzniks the same age as Koestler looked decades older, their cheeks jaundiced from malaria and sunken with hunger. Their austere teetotalling routine of near-endless labour made the bon-vivant-ish Koestler feel like he had accidentally barged into a monastery on a pub crawl. He proved hopeless at fieldwork or farming, failed at stone removal and fruit picking, and his fellow communards struggled to find chores suited to the German bookworm in their midst. In the end, he was voted down for membership—which proved an immediate disappointment but ultimately a relief to Koestler. He would claim to have stayed several weeks on the kibbutz; another letter suggests that only managed to tough it out for 10 days.

Twenty years later, a much-admired journalist and novelist, Koestler returned to the kibbutz and admitted to its members, at a party hosted in his honour, that, yes, he had been a total failure as a settler and deserved to be shown the door. Still, while his restless curiosity had taken him elsewhere, he experienced a pang of nostalgia for the commune that had evicted him. “When I neared the kibbutz,” he wrote, “I felt that, despite the darkness, I had returned to the specific location in the homeland that I could refer to as home.” On that same trip, he visited a number of other kibbutzes to as research for a novel. Joseph, the hero of Thieves in the Night, would share the ironic distance of the author but prove to be a hardier kibbutznik. Through his character, Koestler would get to both relive and rewrite his stillborn experiences as a bumbling volunteer.

Linguist and political critic Noam Chomsky—later a vocal opponent of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza—stayed for six weeks on Kibbutz Hazorea, near Haifa, in 1953 with his wife, where he found a “functioning and very successful libertarian community”. In the years before Israel’s independence, as a young man, he had been deeply interested in anarchist, left-wing politics, and in the socialist vision, shared by many kibbutzniks, of Palestine as a binational state for both Arabs and Jews. He harboured vague aspirations of moving to Israel, joining a kibbutz, and working at Arab-Jewish cooperative efforts. He had no plans, at the time, for an academic career, and his brief stay on Hazorea was a test run for possible immigration to a kibbutz. He worked the fields and found much to admire in the simple life of the commune, as well as the intellectual discussions with the German founders of the community.

But some of the members’ ideology didn’t sit well with the free-thinking young Chomsky, especially how the hardcore Marxists in Hazorea defended the anti-Semitic show trials then going on in the Communist Eastern bloc. Still, Chomsky figured, after returning to the States, that he would return to the kibbutz—his wife did, for a longer stay. But then a research opportunity at MIT and the chance to explore his linguistic interests kept him in the States. The kibbutz lost a bookish fieldworker; the world gained a scientist who would transform our understanding of the human acquisition of language.

Years later, in an interview, the hyper-rational Chomsky sounded ambivalent, even wistful—or as wistful as he must get—about the lost promise of the kibbutz and his brief, youthful experience as a volunteer. “In some respects, the kibbutzim came closer to the anarchist ideal than any other attempt that lasted for more than a very brief moment before destruction, or that was on anything like a similar scale. In these respects, I think they were extremely attractive and successful; apart from personal accident, I probably would have lived there myself—for how long, it’s hard to guess. But they were embedded in a more general context that was highly corrosive.” Even anarchist utopias couldn’t protect their ideals from the outside world.

|

| Borat models 80s-era kibbutz couture |

The nation of Israel changed, irrevocably it now seems, in 1967 in the aftermath of its lightning victory over the massed Arab armies in the Six Day War—and the persistent dilemma of what to do with the Palestinian territories it then occupied. That year also changed the kibbutz movement, by swinging open the gates of these communities—which had always sworn to rely only on the labour of its own members—to volunteers from around the world. Army-aged members had been called up into reserve service during the tense prelude to the war; their positions in the fields and the factories needed to be filled, or the kibbutz economy—and much of Israel’s—would slow to a crawl. The first wave of patriotic Jews from the Diaspora were later followed by hordes of adventure-seeking non-Jews, hippies who had heard rumours of communes in the hills and the deserts of Israel, young Germans burdened by the collective guilt of the Holocaust, and then other backpackers over the next two or three decades.

Actress Sigourney Weaver joined the wave of young volunteers who came to Israel’s aid from America, Britain and other countries in 1967—although her experience on a kibbutz didn’t quite match her imaginings. “I dreamt we’d all be working out in the fields like pioneers, singing away,” she remembered. “We were stuck in the kitchen. I operated a potato-peeling machine.” That assignment nearly ended her acting career before it began; one morning, the peeling machine started coughing and then erupted, showering her with potato shrapnel, as cockroaches swarmed the sudden windfall. “It was one explosion after another,” the star of Ghostbusters and the Alien movies later recalled. “It should have put me off science fiction forever.” Fortunately, it didn’t.

British actor Bob Hoskins, then 25, also volunteered in 1967, and fell in love with the physical work, the sound of the bird calls at sunrise, the romance of rural life. He wanted to remain as a member—except for one hitch. “I was happy being a kibbutznik but they said to me, ‘You gotta join the army’ and I said, ‘But I’m not Jewish’, and they said, ‘It don’t matter’, so I left.”

In 1971, a reedy-limbed, bespectacled, 17-year-old Jerry Seinfield did two months on a kibbutz near the northern Mediterranean coast on a get-to-know-Israel summer program. He hated it. “Nice Jewish boys from Long Island don’t like to get up at six in the morning to pick bananas,” he later recealled. “ All summer long I found ways to get out of work.”

A year later, Sandra Bernhard had a more positive experience as a young volunteer. She spent eight months on Kibbutz Kfar Menachem, which she claimed helped to toughen her up for the shark pit of auditioning in L.A. (Nearly 30 years later, she performed a cabaret show of songs, comedy and conversation called “Songs I Sang on the Kibbutz”.)

Simon Le Bon, later the lead singer of Duran Duran, kipped for three months in Kibbutz Gvulot in 1979 (and later penned a song called “Tel Aviv”), and his dorm bed was later preserved as a shrine for fans of the dreamy-eyed, swooping-haired, new-wave icon.

Sacha Baron Cohen had been raised in an Orthodox family in London and came, with fellow members of a Zionist youth group, to volunteer on Kibbutz Rosh Hanikra, where Israel’s Mediterranean coastline meets the border with Lebanon. I like to imagine what the kibbutz’s Purim Festival was like when the prankster who became Ali G, Borat and Brüno lived there. Alas, he has never dropped his many personae to talk about his kibbutz experiences, nor has any video evidence surfaced of his stay as a volunteer there.

Aug 23, 2011

One of the knocks against the kibbutz philosophy, from critics, was that its communal economy was “unnatural”. Evolution, they argued, didn’t breed self-interested Homo sapiens to be self-sacrificing Homo kibbutzniks. Natural selection would never favour a genetic predisposition to help others first. That, at least, was the position of “social Darwinism”—the (often crude) application of evolutionary biology (and what Herbert Spencer called “survival of the fittest”) to understanding human society. Competition—at the level of the individual, the species or the “selfish gene”—must underpin the process of evolution.

There’s one catch. Human societies are based, to greater and lesser degrees, on cooperation—on what Peter Kropotkin, the biologist-cum-anarchist, called “mutual aid”. So, too, are many non-human species, from apes to ants. In fact, every multicellular organism is the result, at a basic level, of cooperation among specialized cellular mechanisms working together to create a more powerful whole. So how do scientists make these real-world acts of cooperation gibe with the Darwinian theory of natural selection?

A recent book called SuperCooperators: Altruism, Evolution, and Why We Need Each Other to Succeed offers a thorough and engaging overview of the subject, as well as a strong case for how cooperation is a key component of the evolutionary process. It’s written by Austrian-born mathematical biologist Martin A. Nowak (in cooperation with science journalist Roger Highfield), an intimidating super-brain who has been on the faculty of Oxford, Harvard and Princeton, and has collaborated with a wide range of leading academics and bright up-and-comers to apply the tools of “game theory” to understand how different cooperative strategies might evolve. (Check out a YouTube video of him here.)He begins with a look at the “Prisoner’s Dilemma”—a game-theory exercise that poses an obstacle to cooperation. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma (much like the Tragedy of the Commons), “rational” self-interested players will choose to forgo cooperation, even when it would ultimately benefit them more. To encourage the “irrational” choice to cooperate, notes Nowak, “natural selection needs help”. He identifies the five mechanisms that can, under certain conditions, encourage cooperation—and notes that only human beings can access all five.

For a long time, the mechanism of “kin selection” (or “inclusive fitness”) was thought to explain away altruism: organisms cooperate so that their “selfish genes” can replicate either through themselves or close relations that carry the same genes, too. Altruism, in this view, is just selfishness at the genetic level. Nowak argues that kin selection, though, only applies to a select number of situations.

A second mechanism is—most obviously—”direct reciprocity” or “repetition” (known in game theory as “tit for tat”), wherein individuals might cooperate if it’s likely that they will meet again and reap the benefit of a favour in return. A third mechanism involves the extension of reciprocity from direct to indirect via a reputation economy. Here, individuals are willing to act altruistically and promote cooperation based on the reputation for similar behaviour in another individual. This complex form of cooperation requires (or rather, co-evolves with) language and a sense of a public identity—what we know as ”society”. Here, we begin to see the logic of kibbutz communalism—the role of gossip and reputation in a small community to promote and enforce cooperation and keep so-called “free-riding” (ie, the tragedy of the commons) to a minimum.

The last two mechanisms are similarly complex. One is “spatial selection”—the fact that cooperation can evolve and expand, even without indirect reciprocity, as individuals coalesce into clusters and networks of cooperative behaviour. Finally, “group selection”—long dismissed by most biologists—now stands on firmer ground as a theory. Nowak also calls it “multilevel selection” to underline that direct and indirect reciprocity can encourage natural selection to operate not simply at the level of the individual but also at the level of the community or the tribe. But he notes: “This cooperative mechanism works well if there are many small groups and not well if there are a few large groups.” That caveat offers food for thought when considering the issue of sustainable size for livable cities, communal societies and cooperative organizations.

Nowak brings a sense of urgency to his final chapter, where he notes that looming environmental crises—the Tragedy of the Commons on a global scale—make the need for human cooperation imperative. We have the tools. We are genetically programmed, in the right circumstances, to benefit from cooperation. There is nothing stopping us…except the paradox of the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the short-sightedness of immediate gratification over the long-term benefits of cooperation.

“Humans are SuperCooperators,” Nowak concludes. “We are able to draw on all five mechanisms of cooperation. In particular, we are the only species that can summon the full power of indirect reciprocity, thanks to our rich and flexible language. We have names and with them come reputations that can be used to help us all to work more closely together. We can design our surroundings… to achieve more enduring cooperation.”

We just need to find the collective will to do so.

SuperCooperators: Altruism, Evolution, and Why We Need Each Other to Succeed. Martin A. Nowak, with Roger Highfield. Free Press, New York, 2011.